11. Up There at Capocabana

____________________

I spent many days in the chapel, and when I left in the evenings I would take a bundle of things and spend all night looking through them in my grandfather’s study, beneath the green lamp, with the radio on (as I now believed), to fuse what I was listening to with what I was reading.

The shelves of the chapel contained the comic books and comic albums of my childhood, not bound, but nicely arranged in ordered piles. These items had not belonged to my grandfather, and their dates started in 1936 and finished around 1945.

Perhaps, as I had already imagined from my conversations with Gianni, my grandfather was a man from another era and had preferred that I read Salgari or Dumas. So I, to reassert the rights of my imagination, had kept my comics beyond the range of his control. But since some of them went back to 1936, before I started school, that meant that someone else, if not my grandfather, had bought them for me. Maybe there had been some kind of conflict between my grandfather and my parents-"why do you let your son look at that trash?"-but my parents, having read some of those things as children themselves, had indulged me.

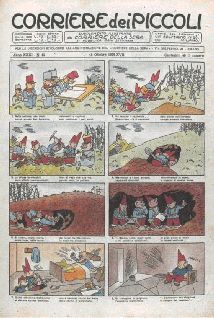

Indeed, the first pile contained several years’ worth of Il Corriere dei Piccoli, the illustrated children’s weekly, and the issues from 1936 bore the inscription "Anno XXVIII"-not of the Fascist Era, but of that publication. So Il Corriere dei Piccoli had been around in the early years of the century, no doubt gladdening my parents’ childhoods-they may even have enjoyed reading it to me more than I enjoyed having it read to me.

In any case, paging through the Corrierino (I instinctively began using that diminutive) was like reliving the tensions I had experienced in the preceding days. Without in any way distinguishing one from the other, the Corrierino spoke of Fascist glories and of fantasy worlds inhabited by grotesque fairy-tale characters. It offered me stories and serious cartoons of absolute Fascist orthodoxy alongside paneled pages that were, by all appearances, American in origin. The only concession to tradition: in strips that had originally used speech balloons, the content had been eliminated, or had been retained merely as decoration: all the stories in the Corrierino had captions-long prose captions for the serious ones, nursery rhymes for the funny ones.

Here follows the adventure / of Signor Bonaventure: this was a story, which certainly touched a chord, about a gentleman with improbably wide-legged white trousers, who, thanks to some completely accidental intervention, always receives a million-lira reward (this in the days of a thousand lire a month) and yet by the next episode is indigent again, awaiting another stroke of luck. Perhaps he was a squanderer, like the oh-so-content Signor Pampurio, who-in each new installment-wants to move to a new apartment. I concluded from the style and the artists’ signatures that both of these strips were of Italian origin, like the strips about Formichino and Cicalone (a diminutive ant and a chatty cicada), Signor Calogero Sorbara (who is always preparing to go on a trip), Martin Muma (who is light as a feather and flies on the wind), and Professor Lambicchi (who invented an amazing superpaint that brings his portraits to life, so that his house is always being invaded by troublesome figures from the past, now a furious Orlando Paladino, now one of the kings from a deck of cards, irritated and bitter about having been removed from his throne in the Land of Make-Believe).

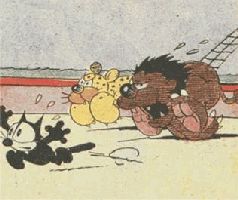

But indisputably American were the surreal landscapes of Felix the Cat, those colonial rascals the Katzenjammer Kids, Happy Hooligan, and Jiggs and Maggie (with those Chrysler Building interiors in which figures emerged from their picture frames on the wall).

It was hard to believe that the Corrierino had brought me the adventures of the soldier Marmittone (dressed exactly like my Soldiers of Cockaigne!) who, thanks to unlucky genes or to the stupidity of decorated generals with risorgimento mustaches, always ended up in prison.

Not much of a warrior or Fascist, this Marmittone. And yet he was allowed to cohabit with other strips that told, in an epic rather than grotesque tone, of young heroic Italians fighting to civilize Ethiopia (in "The Last Ras," the Abyssinians who had resisted our invasion were dubbed marauders) or, as in The Hero of Villahermosa, protecting the flanks of Franco’s troops against the ruthless Republicans in their red shirts. Of course this last strip failed to inform me that although some Italians were battling alongside the Falangists, others were fighting on the other side, in the International Brigades.

Next to the Corrierino collection was a stack of Il Vittorioso, another weekly, along with some of its large color albums, dating from 1940 on. At around eight years of age then, I must have demanded grown-up literature, with speech balloons.

Total schizophrenia there too, with the reader going from delightful episodes in Zoolandia, among characters such as Giraffone the giraffe, Aprilino the fish, and Joj`o the monkey, or from the mock-heroic adventures of Pippo, Pertica, and Palla, or of Alonzo Alonzo (Alonzo for short), who was arrested for giraffe theft, to celebrations of Italy’s past glories and to stories directly inspired by the ongoing war.

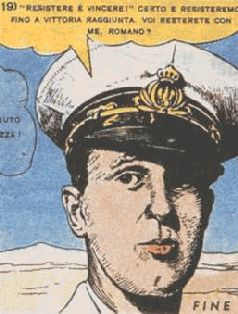

The ones that affected me most were those about Romano the Le gionnaire, because of the engineer-like precision of the machines of war, the airplanes, the tanks, the torpedo boats and submarines.

Made sharper by having revisited the conflict in the pages of my grandfather’s newspapers, I was now able to match up the dates. For example, the story "Toward I.E.A." began on February 12, 1941. Just a few weeks before, the English had mounted an offensive in Eritrea, and on February 14 they would occupy Mogadishu in Somalia, but despite that Ethiopia still seemed to be solidly in our hands, so it was a good time to move our hero (who till then had been fighting in Libya) to the East African front. Sent on a secret mission to deliver a confidential message to the Duke of Aosta, then commander in chief of the Italian East Africa forces, he traveled from North Africa across the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Strange, given that radios existed then and that, as it turned out, the message was in no way confidential (its contents: "Resist and Triumph"); it was as if the Duke of Aosta were simply amusing himself. In any case, Romano traveled with his friends and had various adventures with savage tribes, English tanks, aerial dogfights, and whatever else allowed the artist to make sheet metal shine.

By the time of the March issues, the English had already penetrated deep into Ethiopia, and the only person who seemed unaware of that was Romano, who entertained himself along his route by hunting antelopes. On April 5, Addis Ababa fell, the Italians were regrouping in Galla-Sidamo and Amhara, and the Duke of Aosta was fleeing toward Amba Alagi. Romano continued on straight as an arrow, even taking time to capture an elephant. He and his readers probably thought he was still on his way to Addis Ababa, though by this time the Emperor, deposed exactly five years earlier, had returned. It is also true that in the April 26 issue, a rifle shot shattered Romano’s radio, but that meant that up until then he had one, and so it was unclear why he was not up-to-date on current events.

In mid May, the seven thousand soldiers at Amba Alagi, out of provisions and munitions, surrendered, and the Duke of Aosta was taken prisoner with them. The readers of Il Vittorioso might not have known that, but the poor Duke of Aosta at least should have noticed; instead, Romano meets him on June 7 in Addis Ababa, finding him fresh as a daisy and radiating optimism. Indeed, the Duke reads Romano’s message and affirms: "Of course, and we will resist until victory is achieved."

Obviously, these panels had been drawn months earlier, and despite the course of events the editors of Il Vittorioso lacked the courage to cut the series short. They went forward believing that Italy’s children had remained unaware of all the dismal news-and perhaps they had.

The third stack was my collection of Topolino, a weekly dedicated primarily to the exploits of Mickey Mouse (a.k.a. Topolino) and Donald Duck, though it also included stories about brave Balilla Boys, such as "The Submarine Cabin Boy." I was able to trace, through the volumes of Topolino, the transition that began around December of 1941, when Italy and Germany declared war on the United States-I went to double-check my grandfather’s newspapers, and indeed that was how it had happened; I had thought that at a certain point the Americans had tired of Hitler’s pranks and entered the war, but no, it was Hitler and Mussolini who had declared war on the Americans, perhaps thinking they could dispose of them in a matter of months with the help of the Japanese. Since it would clearly have been difficult simply to dispatch a platoon of SS or Blackshirts to occupy New York, we had, for several years already, been waging war in comic books, from which the speech balloons had disappeared, replaced by captions beneath each picture. Then-as I must have seen happen in various comics-the American characters simply began to vanish, replaced by Italian imitations, and in the end- and this, I think, was the last, most painful barrier to fall-the famous mouse was killed. The same adventures continued as if nothing had happened, but from one week to the next, without any notice, the protagonist ceased to be Topolino and became a certain Toffolino, who was a human, not a mouse, although he still had four fingers, like all Disney’s anthropomorphic animals, and his friends, though also humanized, continued to go by their original names. How had I taken it, back then, this crumbling of a world? Perhaps with utter calm, given that the Americans, from one moment to the next, had become bad. But was I even aware, back then, that Topolino was American? My life must have been a roller coaster of dramatic turns, but given all the exciting dramatic turns in the stories I was reading, the dramatic turns in the history I was living must have seemed unexceptional.

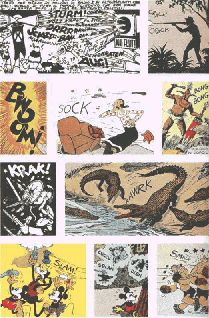

After Topolino I found several years’ worth of L’Avventuroso, and that was completely different. The first issue was October 14, 1934.

I could not have bought it myself, since at the time I was not yet three, and I do not think my parents would have bought it for me, as its stories were not at all suitable for children-they were American comics conceived for an audience of adults, if not necessarily grown-ups. So they must have been issues I had sought out later, perhaps swapping other comics for them. But there was no doubt that I was the one who, several years later, had acquired some of the large-format albums with brilliantly colored covers, on which appeared, like movie previews, various scenes from the story that unfolded inside.

Both the weekly issues and the albums of L’Avventuroso must have opened my eyes to a new world, beginning on the first page of the first issue with an adventure called "The Destruction of the World." The hero was Flash Gordon, who thanks to a scheme

concocted by a certain Dr. Zarkov had landed on the planet Mongo, controlled by a cruel dictator, Ming the Merciless, whose name and features were diabolically Asiatic. Mongo: glass skyscrapers that rose from space platforms, underwater cities, kingdoms stretching through the trees of an immense forest, and characters ranging from the maned Lion Men to the Hawk Men and the Blue Magic Men of Queen Azura, all of them dressed with an easy syncretism, either in outfits that suggested a cinematic Middle Ages, like so many Robin Hoods, or in barbaric loricae and helmets, or occasionally (at court) in the uniforms of cuirassiers or uhlans or dragoons from turn-of-the-century operettas. And all of them, the good and the bad, were incongruously equipped not only with blades and arrows but also with prodigious ray guns, just as their conveyances ranged from scythed chariots to needle-nosed interplanetary rockets in colors as loud as Luna Park bumper cars.

Gordon was beautiful and blond, like an Aryan hero, but the nature of his mission must have astounded me. Prior to that, what heroes had I encountered? In my schoolbooks and my Italian comic books, the valiant men who fought for Il Duce and yearned to die on command; in my grandfather’s nineteenth-century adventure novels, if I was already reading them by that time, the outlaws who fought against society, nearly always for personal gain or out of natural wickedness- except perhaps for the Count of Monte Cristo, who, however, still wanted revenge for wrongs done to himself, not to the community. In the end, even the Three Musketeers, though basically on the side of good and not without a sense of justice, did what they did out of esprit de corps, the king’s men against the cardinal’s men, or for some gain, or for a captain’s commission.

Gordon was different, he fought for liberty against a despot, and though at the time I may have thought that Ming resembled the terrible Stalin, the red ogre of the Kremlin, I could not have helped but recognize in him certain traits of our own house dictator, who held unquestioned power of life and death over his faithful. And so Flash Gordon must have provided me with my first image of a hero-of course I understood that now, following my recent rereadings, not back then-fighting some kind of war of liberation in an Absolute Elsewhere, blowing up fortified asteroids in distant galaxies.

Looking through the other albums, in a crescendo of mysterious flames that had me burning through one issue after another, I discovered heroes my schoolbooks had never mentioned. Tim Tyler and his pal Spud, in the light-blue shirts of the Ivory Patrol, scoured the jungle amid a symphony of pale colors, no doubt in part to keep unruly tribes in check, but primarily to stop the ivory poachers and slave traders who preyed on colonial populations (so many white bad guys against good guys with black skin!), in thrilling pursuit of both traffickers and rhinos, chases in which rifles did not go bang bang or even pum pum, as in our own strips, but rather crack crack, and that crack must somehow have imprinted itself in the most secret recesses of those frontal lobes I was trying to unhinge, because I still felt those sounds as an exotic promise, a finger pointing me toward a different world. Once again, more than the images it was the sounds, or better yet their alphabetical transcriptions, that had the power to suggest the presence of a trail that was still eluding me.

Arf arf bang crack blam buzz cai spot ciaf ciaf clamp splash crackle crackle crunch deleng gosh grunt honk honk cai meow mumble pant plop pwutt roaaar dring rumble blomp sbam buizz schranchete slam puff puff slurp smack sob gulp sprank blomp squit swoom bum thump plack clang tomp smash trac uaaaagh vrooom giddap yuk spliff augh zing slap zoom zzzzzz sniff…

Noises. I saw all of them, paging through comic after comic. I had been brought up since I was little on the flatus vocis. Among the various noises, sffft came to mind, and my forehead beaded with sweat. I looked at my hands: they were shaking. Why? Where had I read that sound? Or perhaps it was the only one I had not read, but heard?

I felt more at ease when later I encountered the albums of the Phantom, the do-good outlaw, sheathed in an almost homoerotic way in his red tights, his face barely covered by a black mask that revealed the feral whites of his eyes, but not the pupils, rendering him all the more mysterious. The beautiful Diana Palmer must have been driven wild with love and must have felt with a shiver, on those occasions when she kissed him, the heroic musculature beneath those tights he never took off (sometimes, wounded by a gunshot, he was treated by his uncivilized acolytes with bandages, always over his tights, which were no doubt water-repellent, seeing as they remained form-fitting even when he emerged from long swims in the steamy South Seas).

But those rare kisses were enchanted moments, for Diana would somehow be quickly whisked away, either because of a misunderstanding, or an aspiring rival, or her other obligations as a beautiful international traveler, and he would be unable to follow her and make her his bride, fettered as he was by an ancestral oath, condemned to his personal mission: to protect the people of the Bengali jungles from the mischief of Indian pirates and white adventurers.

Thus it was that after, or while, encountering cartoons and songs that taught me how to subjugate the fierce, barbaric Abyssinians, I met a hero who lived in brotherhood with the Bandar Pygmies and fought with them against the evil colonialists-and Guran, the Bandar witch doctor, was much more cultured and wise than the unsavory pale-skinned figures whom he helped defeat, not as a faithful Dubat, but rather as a full-fledged partner in that benevolently vengeful mafia.

Then there were other heroes, ones that did not seem particularly revolutionary (if these past few days allowed me to imagine my political growth in such terms), such as Mandrake the Magician, who, though he treated his Negro servant, Lothar, as a friend, seemed to use him more as a bodyguard and faithful slave. Mandrake-or "Mandrache," as he was called in early Italian versions-defeated bad guys with his magic powers and could with a gesture turn an adversary’s pistol into a banana. He was a bourgeois hero, with no black or red uniform, though he was always impeccable in his tailcoat and top hat. Another bourgeois hero was Secret Agent X-9, in his trench coat, jacket and tie, who pursued not the enemies of some regime, but rather robber barons and gangsters, protecting the taxpayers with small, graceful pocket revolvers, which at times seemed surpassingly delicate, even in the hands of carefully made-up blondes in silk dresses, with feather-trimmed necklines.

Another world, one that ought to have ruined the language that my school was trying so hard to make me use correctly, since the anglicizing translations resulted in rough-hewn Italian. But what did it matter? Clearly I was encountering heroes in those ungrammatical albums who differed from the ones put forward by the official culture, and perhaps in those garish (yet so mesmerizing!) cartoons I had been initiated into a different vision of Good and Evil.

There was more. Next to that stack was an entire series of Golden Albums with the early exploits of Mickey Mouse, which unfolded in an urban setting that was obviously not mine (but I do not know if I understood at the time whether it was a small city or a great American metropolis). The Plumber’s Helper (oh, the ineffable Mr. Piper!), Mickey Mouse and the Treasure Hunt, Mickey Mouse and the Seven Ghosts, Clarabelle’s Treasure (here it was, finally,

identical to the reprint edition in Milan, but with the colors ochre and brown), Mickey Mouse in the Foreign Legion-not because he was a soldier or a cutthroat, but because he had agreed out of a sense of civic duty to get involved in international espionage, which led to terrifying adventures in the Legion where he was persecuted by the treacherous Trigger Hawkes and the perfidious Peg-Leg Pete: Mickey Mouse, he’s our guy / in the desert he will die…

The issue I had read most often, judging by the perilous state of my copy, was Mickey Mouse Runs His Own Newspaper: it was unthinkable that the regime would have allowed an article about freedom of the press, but clearly the state censors did not consider animal stories to be realistic or dangerous. Where had I heard "That’s the press, baby, the press, and there’s nothing you can do about it"? That must have been later. In any case, with scant resources Mickey Mouse manages to set up his newspaper, the Daily War Drum-the first issue is full of typographical errors-and continues fearlessly to publish all the news that’s fit to print, despite unscrupulous gangsters and corrupt politicians who want to stop him by any means necessary. Who had ever spoken to me, before that time, of a free press, capable of resisting all censorship?

Some of the mysteries of my childhood schizophrenia began to resolve themselves. I had been reading schoolbooks and comic books, and it was probably through the comics that I had laboriously constructed a social conscience. That was why, no doubt, I had saved those shards of my shattered history, even after the war, when I was able to get my hands on American newspapers (brought over perhaps by soldiers), whose colorful Sunday comics introduced me to other heroes, such as Li’l Abner and Dick Tracy. I doubt our prewar editors would have dared publish them, as their attitude was too outrageously modern and suggested what the Nazis called degenerate art.

Later, having grown older and wiser, was I drawn to Picasso thanks to a nudge from Dick Tracy?

I was certainly not nudged in that direction by the earlier comics, with the exception of Flash Gordon. The reproductions, sometimes made directly from American publications, and without paying royalties, were poorly printed, the lines often blurred, the colors dubious. Nor, needless to say, by those pages in which the Phantom, poorly aped by a homegrown artist after the ban on imports from enemy countries, began sporting green tights and a new personal history. Nor by the cleverly drawn autarkic heroes, probably invented to compete with the pantheon of L’Avventuroso, though they were still generally likable-the massive Dick Fulmine, for instance, with his jutting Mussolini jaw, who pummeled bandits who were clearly of non-Aryan origin, such as the Negro Zambo, the South American Barreira, and, later, the evil criminal Flattavion, a mephistophelized Mandrake, whose name suggested cursed if unspecified races, and who possessed, in lieu of the American magician’s topper and tails, a big shabby hat and a rustic cape. "Take your best shot, my little lovebirds," shouted Fulmine at his enemies in their newsboy caps and their rumpled jackets, and down rained the avenging blows. "This man’s a fiend," the renegades would say, until Fulmine’s fourth archenemy, White Mask, would emerge from the darkness to strike Fulmine on the nape of the neck with a mallet or a sack of sand, and Fulmine would crumple, saying "Da…!" But all was not lost, because, though he might be chained in a dungeon with water rising menacingly, he could flex his muscles and break his bonds, and before long he had captured and delivered to the commissioner (a little round-headed man whose mustache was more bankerly than Hitlerian) the entire gang, neatly packaged.

Water rising in a dungeon must have been a topos of comics everywhere. I felt something like a live coal in my chest as I picked up a Juventus album, The Five of Spades: The Final Episode of Death’s Standard-Bearer. A man in riding clothes, with a cylindrical red mask that covers his head and extends into a scarlet cape, stands, legs apart, arms stretched above him, each limb chained to the crypt walls, as water from some underground source pours into the room, destined to submerge him, little by little.

But in the back of those same albums were other serialized stories, in a more intriguing style. One was called On China’s Seas, and its protagonists were Gianni Martini and his brother, Mino. It might have seemed odd to me that two young Italian heroes would be having adventures in a region where we had no colonies, among Oriental pirates, villains with exotic names, and gorgeous women with even more exotic names, such as Drusilla and Burma. But I certainly would have noticed the difference in the style of the drawings. From the few American strips I had, obtained perhaps from soldiers in 1945, I soon learned that the story was originally called Terry and the Pirates. The Italian version was from 1939, which meant that the Italianization of foreign stories had begun as early as that. I also noticed, in my small collection of foreign materials, that during those years the French had translated Flash Gordon as Guy l’'Eclair.

I could no longer tear myself away from those covers and those stories. It was like being at a party and feeling as though you recognized everyone, experiencing d'ej`a vu with every face but being unable to say when you first met these people, or who they were, constantly feeling the urge to exclaim, How’s it going old buddy, extending your hand but then instantly withdrawing it for fear of making a blunder.

It is awkward, revisiting a world you have never seen before: like coming home, after a long journey, to someone else’s house.

I had not been reading them in any order, neither by date nor series nor character. I was jumping around, going backward, skipping from the heroes of the Corrierino to those of Walt Disney, when it occurred to me to compare a patriotic story with Mandrake’s battle against the Cobra. And in turning back to the Corrierino, to the story of the last ras, which pits Mario, the heroic Vanguard Youth, against Ras Ait`u, I saw an illustration that made my heart stop, and I felt something quite like an erection-or rather something more preliminary, what those who suffer from impotentia coeundi must feel. Mario flees from Ras Ait`u, taking with him Gemmy, a white woman, the Ras’s wife or concubine, who has by now understood that Abyssinia’s future lies in the saving, civilizing hands of the Blackshirts. Ait`u, enraged by the betrayal of that evil woman (who has, of course, finally become good and virtuous), orders that the house in which the two fugitives are hiding be set on fire. Mario and Gemmy succeed in climbing onto the roof, and from there Mario notices a giant euphorbia. "Gemmy," he says, "grab hold of me and close your eyes!"

It is inconceivable that Mario would have wicked intentions, especially at such a moment. But Gemmy, like every cartoon heroine, was dressed in a soft tunic, a sort of peplos that bared her shoulders and arms and part of her bosom. As the four panels devoted to their escape and their dangerous leap documented, peploses, especially silky ones, rise first up the ankle, then up the calf, and if the woman is hanging onto the neck of a Vanguard Youth, and is afraid, her hold cannot help but become a convulsed embrace, with her cheek, no doubt perfumed, pressed to his sweaty neck. Thus, in the fourth illustration, Mario was clinging to one of the euphorbia’s branches, concerned only with not falling into the hands of the enemy, but Gemmy, now safe, was forgetting herself, and her left leg, as if the skirt had a slit, protruded, naked up to her knee, exposing her lovely calf, ennobled and tapered by a stiletto heel, whereas only the ankle of her right leg was exposed-but it was lifted coquettishly, so that her calf formed a right angle with her provocative thigh, and her gown (perhaps as a result of the scorching winds coming off the ambas) clung damply to her body, clearly revealing her callipygian curves and the entire shapely length of her legs. The artist could not possibly have been unaware of the erotic effect he was creating, and no doubt he drew on various models from the movies, or on Flash Gordon’s women, who were always sheathed in skintight garments studded with precious stones.

Whether that was the most erotic image I had ever seen I could not say, but surely (since the date of the Corrierino was December 20, 1936) it was the first. Nor could I guess whether, at four years of age, I had had a physical reaction-a blush, an adoring gasp-but surely that image had for me been the first revelation of the eternal feminine, and indeed I wonder whether after that I was

able to rest my head on my mother’s bosom with the same innocence as before.

A leg emerging from a long, soft, nearly transparent gown, bringing into relief the body’s curves. If that had been one of my primordial images, had it left a mark?

I started going back over pages and pages that I had already examined, my eye now peeled for the most trivial wear in each margin, for the pale prints of sweaty fingers, creases, dog-ears in the upper corners of the pages, slight surface abrasions in places over which I may have run my fingers more than once.

And I found a series of bare legs slipping through the slits of many dresses: slitted the attire of the women on Mongo, including Dale Arden and Ming’s daughter, Aura, and the odalisques that gladdened the imperial balls; slitted the voluptuous negligees of the ladies into whom Secret Agent X-9 was always bumping; slitted the tunics of the sinister girls of the Sky Band that the Phantom eventually defeated; slitted, one guessed, the black dress of the seductive Dragon Lady in Terry and the Pirates… Certainly I fantasized about those lascivious women, while the ones in the Italian magazines revealed legs void of mystery between knee-length skirts and enormous cork heels. Oh as for me, it’s their legs … Which were the ones who awoke the first urges in me-those belonging to lovely milliners’ assistants and domestic beauties on bicycles, or those of women from other planets and remote megalopolises? It seemed obvious that unattainable beauties would have attracted me more than the girl, or woman, next door. But who could say for sure?

If I daydreamed about my next-door neighbor or about the girls who played in the park near my house, that remained my secret, about which the publishing industry neither received, nor offered, any news.

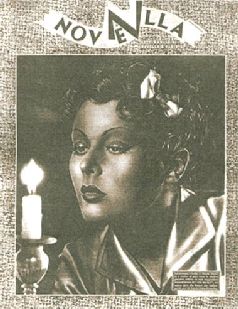

Done with the stacks of comics, I pulled out several scattered issues of a women’s magazine, Novella, which my mother must have read. Long love stories, a few refined illustrations featuring slender ladies and gentlemen with Britannic profiles, and photos of actors and actresses. All of it rendered in a thousand shades of brown-even the text was brown. The covers were a gallery of the beauties of the period, immortalized in extreme close-ups, and at the sight of one my heart suddenly withered, as if licked by a tongue of flame. I could not resist the urge to bend down to that face and touch my lips to its lips. I felt no physical sensation, but that is what I must have done furtively in 1939, at seven, already no doubt in the grip of certain agitations. Did that face resemble Sibilla? Paola? Vanna, the lady with the ermine? Or the others Gianni had sneeringly mentioned: Cavassi, or the American at the London book fair, or Silvana, or the Dutch girl I made three trips to Amsterdam to see?

Maybe not. Certainly I must have formed, out of all those images that had transported me, my ideal figure, and were I to have all the faces of all the women I have loved in front of me, I could extract from them an archetypal profile, an Ideal I have never realized but have pursued my whole life. What did Vanna’s face and Sibilla’s have in common? Perhaps more than appeared at first glance, perhaps the mischievous crinkle of a smile, the way they let their teeth show when they laughed, the gesture with which they straightened their hair. Simply the way they moved their hands would have been enough…

There was something different about the woman I had just kissed in effigy. Had I met her in person I would not have thought her worth a look. It was a photograph, and photos always look dated, lacking the Platonic lightness of a drawing, which keeps you guessing. In her I had kissed, not the image of a love object, but rather the overweening power of sex, the blatancy of lips marked by garish makeup. It had not been a hesitant, nervous kiss, but rather a primitive way of acknowledging the presence of flesh. I probably forgot the episode quickly, as a dark, forbidden event, while Abyssinian Gemmy seemed to me an unsettling but sweet figure, a distant, graceful princess-to look at, not to touch.

But how did it happen that I had saved those copies of my mother’s magazine? When I returned to Solara in late adolescence, already in high school, I must have begun to salvage evidence of what even then felt like the distant past, thus devoting the dawn of my youth to retracing the lost steps of my childhood. I was already condemned to the salvaging of memory, except that back then it was a game, with all my madeleines at my disposal, and now it was a desperate struggle.

In the chapel I had in any case understood something about my discovery of the flesh and the way it both frees and enslaves. Well, that was one way to escape the thralldom of marching, uniforms, and the asexual empire of the Guardian Angels.

Was that all? Except for the Nativity scene in the attic, for example, I had found no clues to my religious feelings, and it seemed to me impossible for a child not to have harbored some, even in a secular family. And I had not found anything to shed light on what had happened from 1943 on. It may have been precisely between 1943 and 1945, after the chapel had been walled shut, that I had stashed within it the most intimate evidence of a childhood that was already blurring in the soft focus of memory: I was assuming the toga of manhood, becoming an adult in the maelstrom of the darkest years, and I had decided to conserve in a crypt a past to which I would devote my adult nostalgia.

Among the many Tim Tyler’s Luck albums, I finally stumbled on one that made me feel I was on the cusp of some final revelation. It had a multicolored cover and was entitled The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. There lay the explanation for the mysterious flames that had shaken me since my reawakening, and my journey to Solara was finally acquiring a meaning.

I opened the album and encountered the most insipid tale ever conceived by the human brain. It was a ramshackle story, no part of which held water: events were repetitive, characters fell instantly in love, for no reason, and Tim and Spud find Queen Loana sort of charming and sort of evil.

Tim and Spud and two friends, while traveling in Central Africa, stumble on a mysterious kingdom in which an equally mysterious queen is the guardian of an ultra-mysterious flame that grants long life, immortality even, considering that Loana, still beautiful, has been ruling over her savage tribe for two thousand years.

Loana enters the picture at a certain point, and she is neither alluring nor unsettling: she reminded me of certain parodies from early variety shows that I had recently seen on television. For the rest of the story, until she hurls herself out of lovesickness into a bottomless abyss, Loana goes hither and thither, pointlessly enigmatic, through an incredibly slipshod narrative that lacks both charm and psychology. She wants only to marry one of Tim and Spud’s friends, who resembles (two peas in a pod) a prince she loved two thousand years before, whom she had killed and petrified when he refused her charms. It is unclear why Loana needs a modern double (especially one who does not love her either, having in fact fallen in love at first sight with her sister), considering that she could use her mysterious flame to bring her mummified lover back to life.

I noticed there, as I had in other comics, that neither the femmes fatales nor the satanic males (think of Ming with Dale Arden) ever sought to ravish, rape, imprison in their harems, or know carnally the objects of their lust. They always sought to marry them. Protestant hypocrisy of American origin, or an excess of bashfulness imposed on the Italian translators by a Catholic government waging a demographic battle?

As for Loana, a variety of catastrophes ensue, the mysterious flame is extinguished forever, and for our protagonists it is good-bye immortality, which must not be such a big deal, given that they have dragged their feet so much in its pursuit and that in the end having lost the flame seems to matter very little to them-and to think they started all that hullabaloo to find it. Perhaps the authors ran out of pages, had to end the album somehow, and could no longer quite recall how or why they had begun.

In short, an incredibly dumb story. But apparently it had come across my path just as Signor Pipino had. You read any old story as a child, and you cultivate it in your memory, transform it, exalt it, sometimes elevating the blandest thing to the status of myth. In effect, what seemed to have fertilized my slumbering memory was not the story itself, but the title. The expression the mysterious flame had bewitched me, to say nothing of Loana’s mellifluous name, even though she herself was a capricious little fashion plate dressed up as a bayad`ere. I had spent all the years of my childhood-perhaps even more- cultivating not an image but a sound. Having forgotten the "historical" Loana, I had continued to pursue the oral aura of other mysterious flames. And years later, my memory in shambles, I had reactivated the flame’s name to signal the reverberation of forgotten delights.

The fog was still, as always, within me, pierced from time to time by the echo of a title.

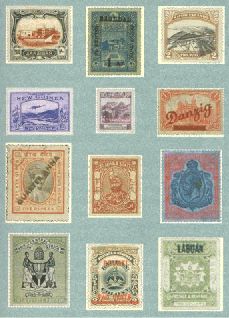

Poking around haphazardly, I picked out a clothbound album, in landscape format. As soon as I opened it I saw that it was a collection of stamps. Clearly mine, as it bore my name at the beginning, with the date, 1943, when I presumably began collecting. The album seemed almost professionally done, with removable pages, organized alphabetically by country. The stamps were attached with hinges, though some-Italian stamps from those years, the discovery of which on envelopes or postcards may well have inaugurated my philatelic period-were thickened, their backs rough, crusted with something. I deduced that I had started out by attaching them to some cheap notebook using gum arabic. Apparently I had later learned how it was done and had tried to salvage that first draft of a collection by submerging the notebook pages in water. The stamps had come off, but had retained the indelible signs of my foolishness.

That I later learned how it was done was evidenced by a book underneath the album, a copy of Yvert and Tellier’s 1935 catalogue, which I had probably found amid my grandfather’s junk. That catalogue was clearly obsolete for the serious collector of 1943, but evidently it had become precious to me, and I had learned from it not the current prices or latest issues, but the method, the technique of cataloguing.

Where had I obtained stamps in those years? Had my grandfather passed them on to me, or could a person buy envelopes of assorted stamps in stores, as they do today in the stalls between Via Armorari and the Cordusio in Milan? I probably invested all of my scant capital with some stationer in the city, one who specialized in selling to budding collectors, and so those stamps that to me seemed straight from fairy tales represented currency. Or perhaps, in those years of war, with the curtailment of international trade-and domestic, too, eventually-materials of some value found their way onto the market, and at low prices, sold perhaps by some retiree in order to be able to buy butter, a chicken, a pair of shoes.

For me, that album must have been, more than a material object, a receptacle of oneiric images. I was seized with a burning fervor at the sight of each figure. Forget the old atlases. Looking through that album I imagined the clear blue seas, framed in purple, of Deutsch-Ostafrika; I saw the houses of Baghdad, framed by a tangle of Arabian-carpet lines, against a night-green background; I admired a profile of George V, sovereign of the Bermudas, in a pink frame against a blue field; the face of the bearded pasha or sultan or rajah of the Bijawar State-perhaps one of Salgari’s Indian princes-subdued me with its shades of terracotta; certainly the little pea-green rectangle from the Labuan Colony was rich in Salganan echoes; perhaps I was reading about the war that was started over Gdansk as I was handling the wine-colored stamp marked Danzig: on the stamp of the state of Indore, I read FIVE RUPEES in English; I daydreamed about the strange native pirogues outlined against the

purple backdrop of some part of the British Solomon Islands. I invented tales involving a Guatemalan landscape, the Liberian rhinoceros, another primitive boat, which filled a large stamp from Papua (the smaller the state, the larger the stamp, I was learning) and I wondered where Saargebiet was, and Swaziland.

During the years when we seemed to be penned in by insuperable barriers, pinched between two clashing armies, I traveled the wide world through the medium of stamps. When even the train connections were interrupted-when the only way to get to the city from Solara would have been by bicycle-there I was, soaring from the Vatican to Puerto Rico, from China to Andorra.

A new flutter of tachycardia seized me at the sight of two stamps from Fiji (how had I pronounced that name?). They were no prettier or uglier than the others. One showed a native, the other bore a map of the Fiji islands. Perhaps I had gone to great lengths to trade for them and so held them dearer than the others; perhaps I was struck by the map’s precision, like a chart of treasure islands; perhaps I had encountered the unheard-of names of those territories for the first time upon those little rectangles. I seem to recall Paola telling me that I had a fixation: I wanted to go to Fiji someday, and I would scour the travel agency brochures, and then in the end put the trip off because it involved going to the other side of the globe, and to go for less than a month made no sense.

I kept staring at those two stamps, and I began spontaneously to sing a song I had listened to days before: "Up There at Capocabana." And along with the song came back the name Pipetto. What was it that tied the stamps to the song, and the song to the name, just the name, of Pipetto?

The mystery of Solara was that at every turn I would approach a revelation, and then I would come to a stop on the edge of a cliff, the chasm invisible before me in the fog. Like the Gorge, I said to myself. What was the Gorge?