Книга: An Owl's Whisper

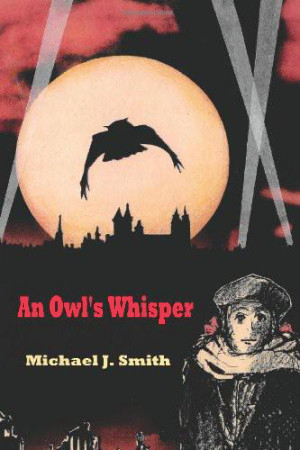

An Owl’s Whisper

Michael J. Smith

This book is a work of fiction. Names and characters, other than historical persons, are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 Michael James Smith

All rights reserved.

Cover art by Robert J. Grabowski

ISBN:1460976312

ISBN-13: 978-1460976319

E- Book ISBN: 978-1-43928-724-8

For my parents.

Acknowledgments

Most novels are born with the assistance of many midwives, each of whom contributes in unique ways to the final product. That was certainly true for my baby, An Owl’s Whisper, and I am pleased to acknowledge their significant contributions. While I gladly share the credit for whatever in the novel works well, I hold my midwives liable for none of its failings.

First and foremost, thanks to my family, Julie, Adam, and Ariel, for unwavering love, support and patience.

My parents, Andrée and Jim Smith, generously shared powerful first person accounts of the occupation and the war in eastern Belgium in the 1940s. Long before that, and more importantly, they imparted an intellectual curiosity and a spark of creativity that unfailingly drove me forward in this writing project and in life.

Ski Grabowski has been particularly devoted to this novel. He did the cover art and tirelessly gave perceptive editorial advice and encouragement, literally from day one.

To members of my writers’ critique group, I owe hearty thanks for their sharp pencils, fine literary sense, and unflagging support. Group members are Venera Di Bella Barles, Sue Bielka, Bill Campbell, Brett Gadbois, Margaret Trent, Harriet Davis, Marcia Rudoff, and Barbara Winther.

My sincere thanks to the kind and perceptive souls who read the novel in varying stages of polish. Each provided helpful, often crucial, feedback. Suzanne Arney, Carole Glickfeld, Jackie Haviland, Robert Potter, Ariel Smith, Julie Smith, Patrice Watson, Trese Williamson, and Kellie Zimmerman.

Finally, I am grateful to people with specific areas of expertise for their generous help. Frank Harding; Hooker County, Nebraska. Danielle Valentiny and Benjamin Stevens; Belgium. Elizabeth Turner and Larry Galpert; child psychology. Norm Hollingshead; opera. Rick Dooling; marketing. Gail Hochman; plot strategy. Sharon Cumberland, Carole Glickfield, David Guterson, Michael Hauge, Priscilla Long, and Bob Mayer; superb Field’s End writing class instructors, all.

Historical context for An Owl’s Whisper

In September 1939 forces of Hitler’s Third Reich invaded Poland, whose allies Britain and France responded with a declaration of war on Germany. In May 1940 German forces drove through neutral Belgium to strike France. In the following weeks, Belgium, Holland and France surrendered and the continental Occupation began. The United States entered the war in December 1941. In June 1944 the Allies made their D-Day landings in Normandy, and by the following September they had pushed Nazi forces back into Germany. Hitler launched a massive, desperate thrust, the decisive Battle of the Bulge, in December 1944. The war in Europe ended in May 1945 with Germany’s surrender.

Contents

Part I: La Folia

On Henri’s Leash

Whispering Owls

Be the Stone

May 10, 1940

Be the Leaf

Filthy and Pristine

Roller Coaster Ride

Red and White

Caspar, Not Marco

Stitches

A Mother

Walks, Together

Poisoned Cheese

Huntress and Prey

Voices in the Vault

Lights in the Night

Prize Fight in Lefebvre

The New Sébastien

Juive, Judas

Part II: Peccavi

The Führer’s Eyes

Smithwycke

Shipped Home in a Coffin

The Changing Tide

Kismet

Henri’s Questions

Crickette and Max

Champagne for Christmas

Geese With Foxes’ Teeth

December 16

th

and All’s Hell

Ardennes Truck Stop

Tigers in the Woods

Obligations

Across From the Tannery

In Fragrant Water

Picnic

Giovanna’s Sin

Two Hundred Twenty-five Pocahontases

A New Forest

Car No. 1120, Compartment Two

New Home, New Hope

Part III: Heads Is Tails

At First Sight

Bluestem Folk

Opera and

Mardi Gras

A Heroine Surely

Snake

Ghost From the Past

In Sickness

The First Day of My Life

White and Red

White and Black

Who Murders a Dying Woman?

Whiskey in the Afternoon

Wallener

An Owl Whispers

Knowing Heads From Tails

Off the Hook

Part I La Folia

On Henri’s Leash

Eastern Belgium, October 1937

Walking from the car, fourteen-year-old Eva Messiaen struggled to keep up with the man clutching her wrist, the man she called Uncle Henri. She looked at Caspar, the small gray dog pattering at her side, and smiled at his floppy right ear, smirking there next to its soldier-straight mate on the left. Henri’s tug pitched her gaze back to his hand and doused the sparkle in her eyes. She peeked at her dog. We’re both on a leash, aren’t we, Caspie? Then she winked. But not for long. She wasn’t surprised when the dog glanced back as if he’d been thinking the same thing.

Eva followed Henri through the green wooden gate of a crumbling wall, to the pathway that led to the Convent School of St. Sébastien. Treading the path’s moss-ringed flagstones, Eva counted them off, alternating French and German in a quiet singsong. “Une. Zwei. Trois. Vier. Cinq. Sechs. Sept—”

Henri jerked her to a halt. “I warned you!”

Tears welled in Eva’s eyes. “But uncle, I was only playing a game with the numbers.”

“Games are for children. As are tears.” Henri touched his swagger stick to her cheek. “Don’t ever forget why you’re here.” As his eyes darted to the convent’s dark windows, he froze. Lips pinched, he slowly lowered the rod. “Oh Eva, don’t cower. Would I strike you over a little slip of the tongue?” He slapped the stick on his leg.

Eva knew better than to answer his question. “It was careless of me.”

Henri tucked the rod under his arm and glanced at the convent. “Just remember—they can’t always be watching.” He smiled like a gambler laying down his winning hand. “You won’t test my patience again, will you?”

She bit her lip. “No, uncle.”

They covered the remaining flagstones briskly and climbed the three slate steps to the convent’s massive, tin-inlaid door. Henri set down Eva’s valise. He put on his pince-nez and glanced at his pocket watch, then he pulled the doorbell cord. When Caspar scratched behind his ear, Henri jerked the thin leather leash from Eva’s hand and tied it to the handrail.

Eva caught her reflection in the long window next to the door. She glanced down to the embroidered bottom of her cream-colored dress, showing beneath the hem of her gray wool coat. And up to her slender face, framed by oak-blond tresses that spilled from of her maroon beret and tumbled over the black velvet of her collar.

When Caspar whimpered, Eva stooped to pet him and saw Henri tapping his toe as he did so often. Nothing was ever quick enough for him. Or good enough. The tapping was a physical echo of the impatience she’d seen early that morning as they sat waiting in the car as Pruvot, his driver, changed a flat tire. To fill the time—every minute must be full, according to Uncle—he had quizzed her on minutia of the history and geography that gave their destination, the village of Lefebvre, its centuries-old status as a carrefour, its strategic importance. Eva too had been impatient, but just to get a first glimpse of her town.

Even with the delay, they had arrived while the village was still sleeping. With Henri as guide, she spent the morning studying Lefebvre’s every nook, even pacing off distances. She sketched it all in her notebook. Henri made a special point of the grand stone bridge, the Pont de Pierre, spanning the River Meuse. He repeated what he’d been telling her all along. “Like the Rhine, the Meuse is a wall dividing, dominating the land of northern Europe. The Pont de Pierre and the bridges in Liege and Namur are gates in the wall. Who controls these gates, controls Europe.” Before they left Lefebvre, he tested her to be sure she’d committed every detail of the town’s layout to memory.

After finishing in the village, they’d made a stop on the drive to St. Sébastien so Henri could show her a hillside path overlooking the military post and materiel warehouse at a road-rail intersection just outside Lefebvre. They counted the men of the Belgian army garrison lounging there in the yard, smoking and playing cards. Then, as they approached St. Sébastien, Henri gripped her arm and said, “The army post, the bridge, the transport lines. That’s why Lefebvre matters so. We’ve shown much trust, placing you here, Eva. Be worthy of it.”

The sound of the convent door groaning open snapped Eva’s attention back to the moment. A tiny, young nun, panting for breath, stood in the doorway. Sister Mouse. Her size, her face, her scuttling way made clear to Eva she could have no other name.

Sister Mouse wiped her hands with a small towel and nodded repeatedly. “Oh, Monsieur Messiaen, forgive my tardiness. I was pulling bread from the oven. What a pleasure to see you on such a lovely autumn afternoon. Won’t you come in?”

“Thank you, Sister Martine.” Henri removed his gray bowler and eased Eva into the dark corridor before him.

Eva closed her eyes and silently mouthed Martine, not Mouse.

After smiling at Eva and glancing at the valise, Sister Martine’s gaze stuck on Monsieur Messiaen. She looked honored to have shown him in. Eva had seen it before. They all fall for him. She thought about what it was that snared them. Not physical stature—he was slight. Eva glanced at his round face, sandwiched between a shiny, bald pate and a red bowtie and starched collar. Glanced at the carefully-trimmed moustache riding over a mouth tight and gray as a pencil line. At the small ears that looked pinned to the side of his head, and the eyes sparkling like quicksilver behind his pince-nez. The gold watch chain decorating the vest of his blue flannel suit, and the red rosebud boutonniere on his lapel. She put it all together—he had the look and bearing of a prime minister.

Henri cleared his throat.

The nun’s eyes fluttered. “Oh, excuse me, Monsieur. You’re here to see Mother Catherine?”

“If that’s possible.”

“But of course, Monsieur. For you.” The nun opened the door to a small room off the corridor, and her tiny hand, extending from the broad sleeve of her habit, arced an invitation. “If you and Mademoiselle would please make yourselves comfortable in the reception parlor…” She scurried off into the darkness.

They sat on a maroon-striped sofa. Eva stared at the swagger stick in her uncle’s hand. She wanted to memorize its physical details. So that the next time she caught herself admiring his cleverness or his dedication to the cause, she could picture it and recall what he really was.

A glare from Henri brought her back to the moment. Careful not to turn her head, she let her gaze wander the dark paneled walls and ceiling: The walnut desk and chair across the room. The old wall clock with its carved frame and cream-colored face and plodding tock, tock, tock. The doe eyes of the sad lady in blue and gold in the age-cracked painting that hung above the desk. The cross over the door.

Eva was reflecting on the face of the crucifix’s Christ-figure, so fatigued, so forlorn, when a stately nun—the antithesis of Sister Mouse—swept into the room. She offered Henri her hand, nodding a genteel bow. “Ah, Monsieur, how nice to see you again.” The gesture was more storybook chateau than rustic convent school. Eva imagined a newsboy, hawking papers on a busy corner the day this nun took her vows: Extra! Extra! Read all about it! Princess Trades Crown for Veil. Is Banished to Belgian Backwoods. Extra! Extra! Eva coughed to suppress a smile.

“Mother Catherine, allow me to introduce my niece, Eva, unfortunately just last month orphaned in her hometown of Reims.”

Eva curtsied. She kept her gaze down as Henri had directed. Until Mother raised her chin with a fingertip.

“Mother,” Henri said, drawing the nun’s focus back, “I require your help.”

“Monsieur Messiaen, you’ve been so generous to us this past year, you’ve only to ask.” Mother’s fingertips migrated to Eva’s cheek as she turned back to her. “You have our sympathy, my dear.”

Eva chanced a smiled Thank-you.

“You see, Mother,” Henri said, “I promised my dear brother that I would attend to Eva if ever the need arose, and alas, so it has. If you were to take her, she’d be properly schooled and I could visit often. I’d insist on making another contribution to fund your important work. Shall we say six thousand francs?” He took out his checkbook and a thick ivory fountain pen.

The nun’s lips moved silently. “Oh, Monsieur, it would be a pleasure to have dear Eva here at St. Sébastien. And such a generous donation would mean so much.”

Henri raised a hand, silencing Mother Catherine. “There is one thing. I hope it shan’t be a problem. Eva loves to walk in the countryside. For her to have these little walks, perhaps before classes in the morning—that wouldn’t be a problem, would it?”

“But of course it wouldn’t. I encourage a healthy regime for every girl.”

Henri bent to write the check. When Eva tugged at his sleeve, he scowled. “Oh yes, there’s Caspar, Eva’s mutt. It’s just outside. Might you keep the dog, too? Apparently it’s quite dear to her. Maybe it could stay in the old stables and be fed with table leavings?”

“Caspar? We’ve never had a male resident at St. Sébastien. But what rule has no exception? Certainly we welcome Monsieur Caspar, too, if he matters so to Eva.”

Caspar staying, Henri leaving! Eva felt like singing it.

“It’s settled then,” Henri said as he handed Mother the check. He turned to Eva. “Now, my little sweet, come walk your uncle back to the motorcar and see me off.”

Stepping from the convent door into the autumn air, Eva and Henri heard the squeals of the dozen girls playing soccer in the grassy area near the stables. Weaving through the mob with the ball was the small nun, Sister Mouse, a whirlwind despite her heavy habit.

Eva paused to watch.

Henri put his hand on her shoulder. “You’d like to join the game, wouldn’t you?”

“Oh uncle, could I? It would be the perfect chance to meet some of…” Eva felt her uncle’s grip tighten. She turned slowly to face him.

“Christ, Eva, here just forty minutes and already you forget everything.” Henri leaned close to her. “You are not to be social. Not to join in. You must be invisible—so dull no one cares to notice you. Can I make it any clearer? Be plain wallpaper, damn it.”

Eva jerked her shoulder from his grasp. “Half the time you tell me I’m special. Selected from hundreds, you say. The other half, it’s ‘Eva play the dolt.’”

“You are special,” Henri growled. “You and my other girls. How many times must I explain? Special enough to seem dull as dishwater—” He grinned. “—while secretly seeing and hearing everything. You’re so much more than those you deceive. Why can’t that be enough?”

Eva glanced back at the girls. “Should I be proud that I deceive them, uncle?”

He squared his shoulders. “What’s the difference between a lie and the truth? Tell me! They’re the same. Both just…sounds. Mere vibrations in the air. What matters is the outcome. Remember this, young lady—deceit in the cause of progress is good. Be proud of what you’re doing.”

“Yes, uncle.” Eva closed her eyes. “But playing…is it a sin?” She shrugged. “Look at them. It’s natural.”

Henri looked incredulous. “Playing…natural? It’s childish! A luxury.” He turned to the side and spat. “A weakness. You don’t need it. Not with so much to do.”

“Perhaps I don’t need it—” Eva looked down, then back at Henri. “—but I want it.”

Henri’s face turned scarlet. “You should be ashamed! Selfish worm. You speak of the importance of our cause, then you put your own little wants first.” He dabbed his forehead with a silk handkerchief and suddenly looked tender. He gently brushed her cheek. “Eva, commitment is hard, but you’re strong. You can do it.” He wiped her tear with his thumb. “I can depend on you, can’t I?”

Eva opened her mouth to speak but stopped. She swallowed and bowed her head. “I’ll do whatever the cause requires.” She looked squarely at Henri. “Depend on me, uncle.”

Henri nodded sharply. “Good.” He glanced at the soccer players. “We’ll leave playing to our enemies.”

Whispering Owls

For two and a half years, Eva remained true to her pledge to be plain as wallpaper. But by March 1940 her resolve was flagging. Perhaps it was the new decade’s dawn. Perhaps it was the springtime air. Being on Henri’s leash now seemed like parroting Latin declensions—not so much difficult as pointless. And approaching her seventeenth birthday, she’d had enough.

One sunny morning, on her way to the stable to pick up Caspar for a walk, she spied a soccer ball left out from the previous day’s recess. Eva turned her face to the sun and felt its warm caress. She filled her lungs with crisp springtime air. And she decided that today she’d leave her notebook in its hiding place behind the loose stone in the stable wall. She picked up the ball and ran into the building to fetch her dog.

On the walk Eva and Caspar kept the ball moving ahead of them. Until a noisy squirrel in an oak on the edge of the convent grounds snatched the dog’s attention. He dashed to the tree and stood barking with his front paws on its trunk. The fox-red squirrel, keeping just beyond reach, railed back. Eva sat in the sunshine, tossing the ball and watching the stymied duo. She squeezed the ball and felt it pushing back, as if it loathed being flat. In that instant, she knew the contest in her hands reflected the one playing out in her heart since she’d arrived at St. Sébastien.

“Monsieur Le Ballon, no one makes a crêpe of you without a fight. I admire that. But you’re lucky. They never call selfish for following your nature by keeping round.” Eva tossed the ball up and caught it. “Uncle’s always prodding me. ‘Be the trudging ant,’ he scolds. Well, I’ve done it his way for two and a half years, and I’ve had it.” She heard a flutter in the trees and looked up to see small birds flitting from limb to limb, their chirps tinkling like tiny bells. Free. “The wren in flight…that’s me!”

Caspar romped back and licked Eva’s cheek. She nestled her dog and said, “I won’t cry for my childhood. What’s lost is lost. But starting today, things change. Before I accepted what uncle said—that next to the greater good, my wants are nothing. But being myself isn’t betrayal. I needn’t be his plain wallpaper. I can serve the cause without being a good little ant. Maybe even do it better.” She smirked. “And what he doesn’t know can’t hurt me.”

Eva was good to her word. Overnight, like a butterfly emerging from her cocoon, she blossomed socially. It started with stories.

At precisely 9:30 each evening Sister Arnaude padded through the dormitories calling, “Lights out.” It had been so at St. Sébastien forever and the nun’s cry marked the day’s end—until the March 1940 night Eva established Le Cercle de la Chouette Chuchoteuse, the Club of the Whispering Owl. Each of the twenty-six girls in the upper sleeping dorm was soon a member. On those evenings after she formed Le Cercle, it was lights on at 9:35, when Eva lit a candle and called the Whispering Owl members to order in its glow. She’d bring the candle flame close to her face and tell a story.

Some of her first tales were prompted by talk Eva heard one night just after lights out. Danielle, the youngest girl there, had just returned from a visit home. “My cousin told me they make nuns out of naughty little boys! For punishment, they cut off their pee-pees and send them to a convent. Is it so?”

Giggles and howls erupted through the dormitory. An older girl, Isabelle from Paris, said, “That is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. How can you be so dumb, Dani? Everyone knows nuns were homely girls, donkeys who couldn’t catch a husband.”

The girls went along with that, even those who worried they might have a bit of the donkey in them. But not Eva. For her, being popular was enough to make a contention suspect. “Did you say homely, Isabelle? What about Mother Catherine? She’s as far from homely as can be. As for boyfriends, I know of a convent of nuns who all had them.” She looked up at the ceiling and tapped her lips with her index finger. “One of the beaus was even a famous artist. Gather around while I light my candle and you’ll hear about the convent school of St. François D’Assisi. It was located in a hollowed-out fir tree in the deepest part of the Ardennes forest. Four nuns taught there: Mother Swan, Sister Mouse, Sister St. Bernard, and Sister Tortoise. And the students were all tiny wrens.

“Mother Swan was the head of the school. She’d grown up in Paris, a Swan-King’s daughter and spent her days swimming serenely on the River Seine. One spring day Monet espied her there and fell in love. Each morning, he’d watch her glissade into the water. Watch her body slip over the surface as if she were weightless. He couldn’t take his eyes off her.”

Camille was licking the tip of her brunette braid. “What was she wearing, Eva?”

“Just the sunlight.”

“Nothing?” Camille’s eyes were wide.

“Ah, everything,” Eva said. “All she needed. You see, Cami, she was content with herself. And that fascinated Monet as much as did her beauty. His fascination compelled him to immortalize her contentment, painting her graceful glide through Notre Dame’s reflection on the water. When she left to join the convent of St. François, the story goes that he was so dejected he took to painting only water lilies for the rest of his days.”

Eva scanned the faces of the blanket-draped girls around her. She took the candlelit sparkle of their eyes as a go-ahead.

“In charge of the kitchen was Sister Mouse, a nervous little one, but good with a kettle and a spoon. In her youth, a handsome pigeon named Monsieur Jinx was her beau. After a local cat killed him, Sister Mouse wanted revenge. She moved into the kitchen of a famous restaurant on Brussels’ Grand Place and learned the art of cuisine. She steamed the cat a pot of mussels laced with strychnine. It cured him of pigeon-eating.” Eva winked. “Afterward, guilt drove her to enter St. François. It’s said that everyone there knew her story, and everyone stayed on Sister Mouse’s good side. She slept snuggled in the floppy, furry ear of Sister St. Bernard.”

Clarisse LaCroix, a leggy, freckled redhead from Thieux, had been brushing her hair. Before Eva could begin the story of Sister St. Bernard, she said, “Poisoned food, eh? I had some of that on holiday in Italy one summer.” She grabbed Eva’s candle. “Hey Blondie, you know what animal your fairy tale needs?” Clarisse eyed Mirella, the daughter of an Italian diplomat stationed in Brussels. “Canis italienis! Those Wops—they are animals. You’d think they never heard of hygiene. You see them pissing right into the gutter. Like the other dogs.”

“Clarisse, behave!” pleaded Mirella’s chubby friend, Bébé.

Clarisse glared back and echoed a nasal whine. “Clarisse, behave!”

Mirella jumped up. “LaCroix, bet you haven’t been to Italy since Il Duce came to power. We’re the pride of Europe now!” She put her hands on her hips and thrust out her chin.

Clarisse pushed the candle’s flame toward Mirella and held her hairbrush like a club. “Right, Mirella, and I suppose you’ve made Ethiopia the pride of Africa, too?”

Eva stepped between the two girls, facing Clarisse. “You may choose to admire Mussolini or not. But when the Whispering Owl holds court, she won’t have one girl taunting another.” Eva said it matter-of-factly. “Do behave yourself, Clarisse. Or leave.”

Clarisse blew out the candle and shoved it back at Eva. “Talking owls. A convent of animal nuns. What a pile of merde!” She glanced around the circle of girls. No one met her gaze. Clarisse scowled. “Huh! Go ahead and waste your time. I’ve heard enough.” She stomped off to bed, crawled under the covers, and dramatically pulled a pillow over her head.

Françoise de Lescure leaned to relight the candle. So gangly she was known as Stork, Françoise shared a bond with Eva, one born of their mutual social invisibility. She glanced at Clarisse and whispered, “Careful, Eva. She’s used to running things here.”

Clarisse had been watching from under her pillow. She sat up in bed. “Bet you wouldn’t dare say that so I can hear it, de Lescure.” She shook her head in disgust. “Don’t know why anyone would listen to a dumb Stork.”

Eva faced Clarisse. “I, for one, love to hear her speak. Françoise’s tongue spins out poetry as nicely as Monsieur Kreisler’s violin bow does music.”

“Kreisler.” Clarisse crossed her arms and huffed. “Another kike!”

Eva’s face turned flinty. “At least he’s not in prison. For embezzlement. Like your mother.” Her eyes burned like a leopard’s. “I caught a glimpse of your file in the office one day. No wonder your mother doesn’t visit.”

Clarisse slid to the edge of her bed, but stopped there. Tears welled in her eyes. “Take it back,” she snarled. Then she said quietly, “She’s not in jail.”

“Then tell us why she never visits,” Eva taunted. “Thieux isn’t so far, is it?”

Clarisse glared. “You’re lying.”

“Sure Clarisse, I’m lying.” Confidence danced in Eva’s eyes. “There’s probably a perfectly good reason she doesn’t visit. Come on, tell us why.”

Clarisse turned her back to the circle of girls. She curled up into a ball on the bed facing away and said nothing more.

Eva smiled, victorious. She raised her candle and looked around. “Shall we proceed, girls?”

Bébé tugged on Eva’s sleeve. “I was wondering. About Mother Swan.” She bit her thumbnail. “Since she once had a beau and is so beautiful, maybe she’d still have admirers?”

“Bébé! After they become nuns, they can’t have boyfriends,” Camille said.

“They are people, Camille,” Eva said. “Who can say what goes on in the quiet of their hearts? Anyway, in fairy tales anything goes. So, a beau for Mother Swan? Hmm, let me see.” Eva tapped her index finger on her lips. “Ah-ha! Mother Swan’s boyfriend. There was a fellow who showed up one winter’s day, dressed to the nines and bearing gifts. He had fur white as swan feathers. His blue flannel suit, elegant as a prime minister’s, was decorated with a gold watch chain and a red rosebud boutonniere. He sported a scarlet bow tie and a collar starched stiff as communion wafer. He carried a leather swagger stick—he didn’t ride, but he liked the impression it made. In his sharp teeth he clutched a black and gold Russian cigarette and his eyes danced behind a pince-nez. His name was Monsieur Ermine.”

Bébé looked puzzled. “But an ermine is really just a pretty weasel!”

“A pretty weasel? That’s him, all right,” Eva said.

“Well, how could Mother Swan go for a weasel?”

“The gifts, the regal white fur, the red rosebud. I suppose she couldn’t see beyond them to the teeth.” Eva suddenly felt exhausted. “Girls, it’s late. Next time, I’ll tell you about Sister St. Bernard and Sister Tortoise. And if we have time you’ll hear how the students of St. François started the wren custom of morning song, a practice now delightfully spread the world over.”

As the others were shuffling off, Françoise took Eva’s arm. “How awful about Clarisse’s mother!” She looked at the floor. “You really shouldn’t go snooping in other girl’s files.”

Eva leaned over and whispered, “Between you and me, I didn’t.” She winked. “I made up the embezzlement story.” She poked Françoise’s ribs. “Look, no one ever sees her mother, and Clarisse becomes evasive when people ask why. Way I figure, she must be hiding something. You know, the truth can be more frightening than any fiction, Françie. No matter what fib I made up, I knew only the truth would counter it. I was betting Clarisse couldn’t bring herself to do that.”

Françoise stared in disbelief. “You lied?”

Eva shrugged. “Call it what you like. I wasn’t about to let her get away with what she said about you. I knew how to shut her up, and I did it. Lies that make good are good.”

“Lying is lying, Eva—” Françoise shook her head. “—even when you’re battling a bully.”

“Welcome to the Twentieth Century, dear Françie. People lie all the time. I just made one red-haired tyrant look soft as soufflé. You can’t deny that’s a good thing.”

“All I know is, lying is lying.”

The nuns had all seen Eva’s transformation and marveled at it in conversations among themselves. “Mother Catherine,” Sister Arnaude said, “you always said there was sparkle and glow inside that one, and now it shines forth like Christmas Eve candles. You were right.”

Mother shrugged. “I sensed she was something special. Now it’s there for all to see. What else can I say?”

She did say more to her confessor, Father Celion, Lefebvre’s parish priest and the chaplain at St. Sébastien. Only in the dark medium of confession could Mother voice the truth. “Father, I feel guilty of the sin of vanity and much worse in my thoughts, my musings.”

The priest’s brow rose. “Vanity and much worse? Say more.”

“Father, I refer to my musings about one of our girls.” Mother spoke slowly. Tentatively. “It’s not just me. Everyone’s charmed by her.” She said charmed as if it were sin in itself. “To the other girls—” She was silent for a moment, fighting the urge to say Eva’s name aloud. “—she’s become a sort of pied piper. You recall, Father, our little Danielle l’Hôpital? The one so homesick she’d run away five times? Mademoiselle Piper began telling bedtime fairy tales about a school where the students are small birds, and her stories have so soothed Dani that today she said, ‘Mother, I wouldn’t leave St. Sébastien for anything.’”

Father Celion pursed his lips. “But perhaps you should fret a pied piper. Remember the people of Hamlin who lost their children. Ask them about embracing pipers.”

“I only mean her allure has an air of magic to it. We’ve nothing to fear from my piper.”

“Your piper?” The priest cleared his throat. “I don’t doubt your judgment. I only advise caution as a matter of course. But we digress. It is your conscience we probe.”

“Excuse me, Father. As for me, while I see all the girls as daughters in Christ, I’ve come to see this one as—” Mother closed her eyes. “—As my own daughter. More. I always knew she was special.” Her voice became quick, excited. “But these days when I see her, I flatter myself that I am looking into a mirror. The vanity is staggering, Father. For my conceit is that the mirror is magical and this child is me, twenty-five years ago. Do I want her to have the life I chose for myself? No, for her I wish a secular life: Freedom, romance, marriage. I wish that, because through her I can—” Mother sobbed softly and for a moment was unable to go on. “—I can have those things, too. When I find myself wanting that, I feel I’ve broken my vows.”

Father tugged on his ear, a habit he’d picked up when he stopped smoking. “Let me see if I grasp this. You are happy in your vocation? Do you desire a secular life?”

She sighed. “For me, no. I want no other life.”

“But do you wish to experience a secular life vicariously?”

Mother closed her eyes and inhaled deeply. “I don’t know what I want, Father.” Her voice was gray.

“Mother Catherine, I must say, you flabbergast me! You’ve always struck me as one so in control. One who sees everything so clearly. I never imagined you confused.”

“Father, when I was a girl, Papa used to take me to the opera. My favorite was La Wally. A hopelessly contrived story, but I identified with the little heroine Wally—free-spirited but vulnerable, just like me. Perhaps I entered the convent to rein in the former and vanquish the latter. And I thought I’d succeeded. But lately I’ve felt like a canoe left untethered at the riverbank. I love having Mademoiselle Piper at St. Sébastien, but life would be simpler if she’d never come.”

Another tug of the ear. “My child, you are not helping me know whether you wish the best for this child, for which you should be blessed, or you covet what your vows preclude, for which you need absolution.”

“That I cannot say, Father.”

A tug once more, and a sigh of exasperation. “Lacking the wisdom of Aquinas on this point, I am unable to cut such a fine distinction. I charge you to dwell not on this child’s future, but rather to exalt in your own service to Our Lord. Ask Our Lady to assist you in this by saying an Ave for each of your students and one for me. Now go and sin no more.”

Be the Stone

Mid-afternoon on April 23, 1940, baby-faced Nathalie toddled into Sister Eusebia’s geometry class with a note from Mother Catherine.

The nun put on her spectacles and read it. She removed the spectacles. “Eva, you are to go to the office immediately. It seems your uncle is here.”

Eva gathered her books and hurried out with the eyes of every classmate on her. She ran down the corridor, wondering what could bring her uncle to St. Sébastien on a Tuesday afternoon. He’d come to check on her regularly, monthly or so, since he’d placed her at the school in 1937, but always on weekends. Something was up.

At Mother Catherine’s door, Eva paused for a deep breath then knocked.

Mother opened the door. “Eva, your uncle’s come to see you.”

Henri strode to Eva with head tilted and hands outstretched. After kisses, he put an arm around her shoulder. “My dear, don’t you look fine to your old uncle! Gracious, I think you’ve grown two centimeters this month!” He laughed. “Mother, what are you feeding these girls?”

Mother closed the manila folder on her desk. “I was just showing your uncle how well you’re doing in school, Eva, and telling him how important you’ve become here at St. Sébastien.” She turned to Henri. “We all depend on this one, Monsieur.”

Eva said nothing.

“That’s gratifying.” Henri picked up his bowler and umbrella. “Well, my dear, as I told Mother Catherine, I was in the area, and there is a matter we need to discuss—something Grandfather has planned. Let’s go for a ride on this lovely spring day. Get some fresh air. I’ll have you back by dinnertime.” Henri nodded to Mother and whisked Eva out the door.

They approached Henri’s big, tan Mercedes. The chauffer, Pruvot, stiff in his blue uniform, opened the car door for them. Eva whispered, “Is something wrong, uncle?”

Henri huffed impatiently and leaned toward her. “No, something’s not wrong. I have things to tell you, but not in front of the whole world. Is there a private spot nearby?”

“There’s a meadow next to the mill stream. It’s quiet. I sit there sometimes.”

“Fine. Tell Pruvot the way there.”

They got into the phaeton. Eva said to the driver, “Head toward Lefebvre, Pruvot. Turn left just after the rickety bridge.” The Mercedes eased away from the convent.

They turned onto the lane tracking the stream. Henri pointed with his swagger stick to a shady spot on the bank. “We’ll sit there, Pruvot. Bring the blanket from the boot.”

They walked the ten meters to the stream bank, and Pruvot spread the blanket. Henri told him, “Fine. Now wait with the car and keep a lookout. I don’t want to be disturbed.” He sat and patted the place next to himself, indicating Eva should join him. “Charming spot,” he said as he tossed a pebble into a pool near the shore.

Watching the circular ripples radiate on the water’s surface, Eva felt anxious.

With his stick, Henri flicked an imaginary speck from the blanket. “Mother Catherine chatters on about all you’re doing at the school.” He set the stick down, its tip touching Eva’s knee, and he picked a twig from the grass. “About how the other girls have come to look up to you.” He snapped the twig in two. “What are you thinking? I told you to shrink into the wallpaper, not be the damn chandelier.”

“Uncle, you said I was doing well, keeping my notebook. I like the other girls.”

“It’s not a matter of what you like. Listen, young lady, you have more important things to do than be a cuckoo bird.” He lit one of his black-papered cigarettes. “Look at the stream flowing by. Tell me what you see.”

“Just the sun’s reflection.” Eva brushed a tear from the corner of her eye. “And that leaf floating by.”

“Aha. You notice what sits on the surface. The sparkle. The leaf. But you miss what’s beneath it—an underwater rock. See the ripples just there?” He pointed with his stick to a faint swirl on the water. “I’m sure there is a stone below. And though you don’t see it, that stone influences the flow of the stream infinitely more than does your leaf. You are to be the stone hiding under the surface, not the leaf everyone sees.”

Eva blinked back tears. “But uncle, Mother Catherine’s become a mother to me. And the girls, they’re like sisters. One of them, Françoise, is the best friend anyone ever had. We—”

Henri snapped his fingers in her face. “Merde, Eva, your friends are dolts, aspiring to no more than serving some lout of a husband. And that stupid nun, content in her mysticism.” He shook his head and sighed. “You are so much more than they are, lucky girl.”

Eva looked shocked. “You speak with such contempt of them. We’re working to lift them, too. Isn’t that so?”

“Of course they’ll be better off in the end. They might be too dull to see it now, but they’ll come around.” Henri raised his arms in frustration. He moved his hand before her face and slowly brought his fingers together in a fist, as if grasping air. “Mon Dieu, what’s important, Eva, is your chance to bend history.”

“Must history be bent?” Eva shook her head slowly. “I sometimes think that for me, being normal, having a family, is enough.” Her eyes blazed through tears. She looked away. “More than enough.”

Henri scowled and rapped her knee with his swagger stick. “Listen child, you have no family! No family but the nation.” He used the rod to turn her face to his. “Your own mother tossed you aside like garbage, for Christ’s sake. We took you in. Became your family. The only one you’ll ever have.” Henri’s face went from hard to soft quick as butter hitting a hot skillet. He reached over and tenderly stroked the hair over her ear. “And we count on you now—for the enemy prepares to jab a spear into our heart.” His fingertips lingered on her cheek. “Even as we speak, he schemes to put us under his dusty boot. Do you see that, for now, we all must sacrifice everything for your family’s survival? Sacrifice everything to usher in the new era? Everything?”

Eva’s lip trembled. “I understand, uncle.”

Henri nodded. “Very well.” He looked around to be sure they were alone. “I did come today to discuss something other than commitment. Important events approach. Just this week I learned that the clock has been wound. That La Folia has begun.”

“La Folia?”

Henri rolled his eyes. “The dance. A Sarabande. Don’t those nuns teach you anything? In olden days, La Folia was a tumultuous dance in which tempo and rhythm swept the dancers into a frenzy. When hostilities break out soon, there’ll be a worldwide Folia from which only one side will walk away. It must be your nation, your family, that’s left standing at the dance’s last note. You do understand, don’t you—it’s the highest virtue to do whatever it takes, to kill if necessary, to save your own family?”

“Yes.” With a finger she traced invisible lines on the palm of her hand as if truth were scribed there. “I understand.”

Henri scowled. “You don’t seem convinced.” He reached inside his coat for the knife he kept in the inner breast pocket. He held the ivory handle before Eva’s face and pushed the release. The shiny blade sprang out obediently. “No such qualms infect Monsieur Knife.” He reflected a shaft of sunlight from the blade into Eva’s eye. “Be more like me. I’d gouge out a heart—even yours—without blinking, if the nation’s good required it. That’s true virtue.” He studied her face. “Of course, I have no need to cut you, since you’re committed. Right?”

Eva faced her uncle. “I am committed to my nation—my family—and her cause.” There was no reservation in her voice.

Henri retracted the blade and returned the knife to his coat pocket. “That’s more like it.” He snuffed out his cigarette. “Now listen up. Our foes are preparing to strike. Soon. Keep vigilant for anything suspicious. Remember, yours are the eyes and ears I count on. Yours and those of my girls in Liege and Namur.” He raised his index finger for emphasis. “Above all, watch the Meuse bridge. Remember, the bridge’s gatekeeper controls all of northern Europe. We must be that gatekeeper! Also keep a sharp eye on the Belgian army facility outside Lefebvre. Watch for troops on the move. Especially foreign troops. I need accurate aircraft numbers. Alert me to anything out of the ordinary, no matter how innocent it seems. Got it?”

“Watch the bridge. And troop locations. Report anything extraordinary….I understand.”

“Fear not, we will counterstrike. If it can be mounted, perhaps we’ll even preempt the enemy’s plan. In the next weeks. A defensive war. An honorable war. In any case, it doesn’t change your role: You are my eyes. Understand?”

Eva nodded.

Henri took her hands. “It’s a glorious time you live in, Eva. The nation, your family, counts on you. Nothing else matters.” He stood. “That does it. We go.”

Nothing more was said until Eva was getting out of the Mercedes at St. Sébastien. Henri grabbed her sleeve. “Don’t you let me down!”

When the other girls saw Eva just before supper they asked about her uncle’s visit.

“Uncle just wanted to tell me some plans he has for a big dance party,” Eva said. “Nothing much to do with us here. He told me a story about stones and leaves.”

“A story!” Bébé clapped. “Perhaps you’ll tell it to us after lights out tonight?”

“Perhaps—” Eva was quiet for a moment. “—If I can find a way. I want so much to tell you. Let me think on it.”

That night Eva lit her story-telling candle to convene the Whispering Owls. She brought the flame close to her face. “This is the story of Bleubec, a new-hatched cuckoo chick. Did you know Cuckoo mothers lay then abandon their eggs in the nests of other types of birds?”

“Yes!” Cami said. “Back at home, we have them living in the woods.”

“Is that so?” replied Eva. “I’ll say Bleubec, too, lives very close by. When cuckoo chicks hatch, they are fed and fledged by their surrogate mothers. In Bleubec’s case, she was left with wrens. As different as she looked, you’d think the wrens would see her as foreign, but they did not. She forsook her natural Coo, Coo, Coo trill in favor of a wren’s lilt, and she seemed to fit right in. But little Bleubec wasn’t happy. She was haunted, because her own mother abandoned her. And because she had to live two lives separated from each other by a magic wall.”

Eva bit her lip, as if thinking what to say next. “One life was lived in the secret world of her cuckoo heritage where everything was solid and sturdy like a stone set in mortar. And the other was spent in the world of the wrens, one of freedom and warmth, as soft as a leaf. But soft things don’t last. What Bleubec hated most was the wall of silence between her worlds. She longed to tell the wrens what she mustn’t say—that their world couldn’t last and its passing would be painful, but that the new one, the one of stone, would be best in the end.”

Clarisse interrupted, “Blondie-head, this has to be the worst fairy tale ever. Better stick to your stories about Mother Swan and her silly woodland school.”

The other girls nodded shyly.

Laetitia took Eva’s hand. “It’s just that we like the other stories better, Eva.”

“That’s fine,” Eva said. “Soon I’ll have some new characters for Mother Swan to deal with. Some geese, maybe. You’ll find that more interesting.”

“Geese are funny,” Bébé laughed, pantomiming a goose’s waddle.

“Perhaps,” Eva said, “and if not, I’ll try to make them so.”

May 10, 1940

It was before dawn when the racket woke Eva. For the first few moments, drifting in that hazy transition between sleep and waking, she was angry that her birthday celebration had turned chaotic when the cake burst into flames. Then the haze cleared, and Eva realized that while both celebration and cake had been dreamt, the chaos was real.

“Get up immediately, my flowers!” Agitation frosted Mother Catherine’s voice. “Don’t take time to dress. Carry your school uniform down to the chapel vault. Move quietly and quickly.” The nun helped Estelle, the crippled girl, down the line of beds to the staircase.

Dani sat up in bed. “Mother, is it a fire?” she bawled.

“No, I fear war has come down on us. Now do just as I instructed. Quickly!”

Eva was last in a string of girls heading through the dark dormitory to the chapel. She dawdled, transfixed by the thought that what she’d waited so long for had finally begun: Her nation righteously confronting evil. An effete Europe reborn, cleansed. A day, as Henri put it, “to tell your children about.”

On the stairs she heard a humming sound and stopped at the stairwell window to look and listen. Over several moments, hum turned to drone and then to angry buzz. Growing louder. Coming closer. The sound became a screech. Then Eva heard the staccato tap, tap, tap, tap, tap. Like a distant snare drum. The drumming got closer, louder, more insistent as the screech became a tortured roar. Peering out the window, at first Eva saw nothing but the purple dawn. Then it came hurtling by, so close she jumped back. The spectacle riveted her gaze: Plane, flames, smoke, in that order. It was a biplane, cartwheeling a wild, earthward arc. Its sputtering engine spat sooty licks of flame and belched billows of black smoke. It passed by the window so close Eva could see the pilot, a rag doll pitching about in the open cockpit. As if the air were syrup, the plane seemed to move in slow motion. The drama ended on the hillside pasture beyond the old stable, an orange ball of flame that lit up the garden below the window. An instant later the thud of the explosion smashed into the windowpane, sending a shower of glass shards clinking at Eva’s feet. Stunned by the shocks of flame and blast—and death—she stood frozen, the reflection of orange fire dancing on her face.

It was the barking that unlocked her. Outside, little Caspar raced back and forth between the dormitory door and the garden where he could see Eva in the window.

“Caspie, oh you’re all right. Stay! I’m coming.” Eva stepped back from the window, her slippers crunching glass. She flew down the dormitory stairs like water coursing through a ravine. She bolted through the door to the garden and caught the flying dog. “Caspie!” She held her pet tight. “Oh, the pilot!” Tears filled her eyes. “They tell you about the rosy outcome, but not the thorns along the way.”

Eva heard footsteps on the gravel behind her. She pushed the horror she’d just seen from her mind and wiped her eyes with the sleeve of her robe.

“Child! Thank God I’ve found you!” Sister Arnaude was panting. “What are you doing here? It’s war, you know. Come immediately.” The nun saw the pleading look in Eva’s eyes. “Yes, bring little Caspar. Everyone is waiting for us in the chapel vault.”

“Sister…” Eva’s gaze dropped.

Sister Arnaude looked annoyed. “What is it, child?”

Eva bit her lip. “Who started it?”

“Same as the Great War. The Boche. Always the Boche.”

Eva clutched her dog in the crook of one arm and caught the nun’s sleeve with her free hand. The women headed across the twenty meters to the chapel. As they ran, Eva looked over her shoulder. The horizon-bursting sun had painted the sky pink and lavender. Peaceful. Except for smoke still hanging over the hillside, there was no trace of what minutes before had slashed the heavens. She glanced toward the orchard, looking between the trees for the luminous eyes of her nation’s resolute soldiers. There was only darkness.

The nun tugged the chapel’s massive door open. It swung powerfully, hitting the chapel wall with a clang that echoed through the stone structure. She pulled Eva into the cool darkness of the vestibule and locked the door. Blackness ruled, as if every ray of light had zipped outside just as the door closed. Feeling her way like someone newly blind, Eva followed the nun to the stairs. They spiraled down to the underground vault room, where the nuns and girls of St. Sébastien knelt in the dim light of four candles.

Mother Catherine led the recitation of the rosary. Looking resolute, she nodded to Eva without missing a beat. Icy stares gripped many of the other faces in the vault. The blend of their soft sobs with the communal Ave Marias sounded like the drone of distant aircraft.

Eva wished she could tell them things would be all right in the end.

Sitting with Caspar asleep on her lap, Eva quickly tired of peeling off repetitious Aves and instead surveyed the cavernous vault. She’d been down there just once before and the eerie place fascinated her. As her eyes acclimated to the darkness, she studied the vault’s details: The geometry of the groined arch stonework that came together above her. The tarnished brass candle holders in the four corners of the main chamber, each holding a thick, yellow tallow candle capped with a flickering, flaxen flame. The dark crucifix hanging from the ceiling directly over the small altar. The rack of dusty wine bottles sleeping in the antechamber on the right. The small wooden door on the left, the one Camille said shut in an old nun who’d gone insane. The cold wall stones she’d felt on the stairwell. The flat floor stones, stippled with glittering flecks. The sweet aroma of ancient incense that infused everything. For Eva, the vault’s features were as intriguing as the wrinkles on the face of a centenarian.

When the rosary ended, Mother Catherine gathered the girls around her to sing popular songs from the carefree days after the Great War. When most of the girls joined in, Eva felt the fear in the vault scurry off behind the cobwebs.

After what seemed to Eva an entire day, Mother Catherine sent Sister Arnaude to reconnoiter the outside world. In thirty minutes or so she returned and briefed Mother privately. As they conferred, the vault vibrated with girls’ whispers.

Mother cleared her throat to restore order and spoke in a loud voice that echoed through the chamber. “My flowers, Sister Arnaude has investigated the situation outside. Things seem quite peaceful there, at least for the moment. It is mid-morning. We can now go up to God’s good sunshine and air, but I want you all to stay together in your classrooms. You may read while luncheon is prepared. We hope to hear more news from wireless broadcasts and from Father Celion. When I learn anything, I will inform you.”

The girls were giddy with excitement at the twin prospects of leaving the dank vault and learning what parts if any of their wild speculations and whispered rumors were true. For Eva there was also the prospect of celebrating her seventeenth birthday, that Friday, May 10, 1940.

Be the Leaf

In the older girls’ classroom that afternoon, ancient Sister Eusebia got the students seated and ambled off to settle the younger ones next door. The moment she left, Camille ran to the window, the ribbons on her brunette braids dancing behind her like butterflies. Pointing outside, she shrieked, “There in the orchard! Soldiers on black horses…I think.” Like apples tumbling into a bin, wide-eyed girls scrambled to the window. But they found the orchard tranquil. Other such sightings followed, and in every case, the alarms proved false. The remains of the downed aircraft, its burned hulk and the black-smudged pasture around it, would have fanned the fires of excitement, but they were hidden from view by the old stables and Eva told no one what she’d seen. So quiet, accompanied by disappointment, began to blanket simmering fear. It was in that broth that eight St. Sébastien girls, including Eva and Françoise, clustered together.

Isabelle from Namur was nicknamed Soleil—Sunshine. Pushing her fingers through her auburn hair, she said, “Call me selfish, but I say tough luck if the muddy boots of war tromp someone’s toes. My heart’s racing, and I like it!”

“Call you selfish, Soleil?” said Clarisse LaCroix. “I’d call you easily amused. What have we found? A few crumbs of excitement. Well, it leaves me wanting. Wanting the whole cake.”

Camille fingered her braids. “How’s this for cake, Clarisse? Down in the vault, I dozed off and dreamed of armies moving on the hillsides like swarms of insects. It was tingling terror, seeing those swarms seethe in battle! Then, merde, I woke up.”

Clarisse slipped a hand under Camille’s sweater and ran wiggling fingers up her back, squealing, “Here’s your tingling terror, Cami!”

Camille shrieked, but soon she was laughing with the others.

Simone Jaffre had a voice so tiny her nickname was Trout. “I’d dream of a handsome boy, no matter his side, brought in badly wounded. Imagine cleaning his wounds! Comforting him. Nursing him over many months.” She hugged herself.

“Hey, Troutsie,” jeered Clarisse, “don’t forget to imagine his torrid tongue flicking your ear and his frantic fingers dashing up your linens.”

“Clarisse!” Simone whined.

Isabelle from Paris huffed, “LaCroix, you’re the only one slut enough to think that.”

Clarisse studied her nails. “I doubt it.” She blew Isabelle a kiss and strolled off.

Laetitia took Simone’s arm in hers. “Well I like your dream. My soldier’s a cavalry officer on a white charger. He’s got curly, black hair and a strong mouth. As I nurse him back to health, we fall in love and ride off on his steed, eloping to the Riviera.”

Isabelle said, “For me, his name is Laurent. We too fall madly in love, then have an exquisite, tearful goodbye when he’s sent back to the front.”

Camille giggled. “We’ll have Puccini write you a farewell duet, and I can just see the last scene: Laurent dies at the front with, ‘Isabelle, my love!’ on his lips. And brokenhearted, you die here—of consumption, naturally.” Camille leaned back and coughed softly. She put a hand to her heart and fluttered her eyes closed.

“Cami, you goat!” Isabelle pinched her friend as everyone erupted in laughter.

When the group quieted, Simone took Eva’s hand and looked into her eyes. “And Eva, for what do you long?”

Eva shrugged. “For nothing so romantic, I guess. I feel restless. I just want to get on with it.” Her eyes opened wide, as if she’d startled herself saying all that. “Whatever it is.”

No one asked Françoise what she felt. Good thing, for icy fear froze her tongue.

Just when Eva had given up on a birthday celebration, Françoise pulled her away from the others. “If only we could get back to the dormitory,” she whispered. “I have gifts for your birthday hidden there, and you must have them now, in case something dreadful happens.”

Eva took Françoise’s hands in hers. “We could sneak back there. Sister E. won’t return for a few minutes, and she won’t notice us gone when she does. The next time the others rush to the window, we’ll slip out together. How about it?”

Within five minutes the pair were creeping into the deserted dormitory.

As they sat together on her bed, Eva said, “Your idea to come here is the best birthday gift. Breaking rules—it’s the best antidote for boredom.”

Françoise beamed. “But the plan was yours, Eva.” She turned serious. “Being here with you is wonderful for me, too. It’s like we’ve stepped back in time to a safe world, far from the claustrophobia of the vault and the silliness of the classroom. A world where I don’t expect grim-faced soldiers with rifles and bayonets to burst through the door. One where rumors aren’t passed from girl to girl like influenza. Where, for a moment at least, fears for my family can evaporate like beads of water on a hot stove. Where I can simply celebrate a best friend’s birthday.”

Bathed in a shaft of golden sunlight streaming in through the window, Eva opened her gifts: A tin of candied apricots, a copy of Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, a pair of silk stockings from Françoise’s father’s shop in Brussels. The pair sang a birthday duet, ate sugared fruit, and promised always to be best friends, no matter what.

There was a thud, perhaps the slam of a door. Eva saw fear flicker in Françoise’s eyes. “Françie, we’re sharing my birthday. Caspar is safe. We’ve got excitement. It’s not so bad.” She took Françoise’s hand. “Look, we’re all afraid. That’s uncertainty for you. But it’ll be fine in the end. No matter what army marches in. It may mean a few new rules. The kings, the prime ministers, the chancellors—their lives will turn upside down. But we’re little people, leaves riding a stream. We go from still water to rapids, from eddies to falls, drifting along without trouble—unless we fight the current.”

Françoise forced a smile. “Eva, we are little people, you and I, but I’m not only that. As a Jew, I know if it’s the German army that marches here, there’ll no place for me.”

Eva squeezed Françoise’s hand. “I’ll concede Herr Hitler won’t have you over to dinner. But who wants his old schnitzel and sauerkraut anyway?” Eva grinned. “Life won’t turn black. Like I said, there will be new rules. But so what? It’s no big deal. Be that leaf in the stream! Don’t resist the current.”

Françoise was silent for a moment, as if reluctant to reply. “Sweet Eva. Always wanting to help. Always so wise.” She paused. “Almost always. Eva, I’ll never have a truer friend than you. But I don’t think you understand how different things would become for the two of us. Hearing you now, I can only think of what my father says, The only fish that swims with the current is the dead fish.” Françoise shuddered. “We should get back.” She sounded exhausted.

Eva kissed her on the cheek and whispered, “Remember, we’re leaves, not fish. Chin up.” But even words bright as morning sunshine couldn’t melt the frost on Françoise’s heart.

Back in the classroom, Eva could taste the brew of fear and boredom fermenting there. This calls for a tonic. Another chapter in the tales of the residents of St. François D’Assisi.

Even Clarisse slipped casually in among the listeners when Eva began.

“One morning the wrens were awakened early by a clamor outside their dormitory room in the grand old fir tree that served as the convent school. All atwitter, the wrens sprang from their nests. They were ruffling their feathers and chattering when Sister Mouse burst in. Since the dormitory room was a rather large space for so small a voice to fill, she cleared her throat and squeaked, ‘Students, this morning the forest is full of geese. Their coarse honking assaults every ear. We meet with Mother Swan momentarily on the chapel branch.”

Dani took Eva’s hand. “Who are the geese supposed to be?”

“L’Hôpital, that’s a really dumb question,” Nathalie said. “They’re some kind of soldiers or something. Right, Eva?”

Eva smiled, “Patience, girls. You’ll have an idea, soon enough.”

“In three minutes the wrens dressed and flew down to the chapel. A moment after they arrived, the door latch clicked, and every head turned to watch Mother Swan glide in. She was serene as she spoke. ‘My flowers, as you know, gaggles of geese fill the forest, and they don’t show signs of moving on. Have you thoughts on what to do about our Goose-tapo problem?’”

Danielle squealed, “The Germans. I knew it!”

Eva smiled at Dani and continued. “There were whispered chirps and hushed peeps, but no ideas surfaced. Finally, Sister Tortoise rose in her usual glacial way.

“Mother Swan smiled patiently. ‘Yes, Sister?’

“‘It occurs to me, Mother, that, ignoring certain obvious differences, there is a strong resemblance between a swan and a goose.’

“Mother Swan’s neck stiffened, and her beak opened, and her wings flared out, and a hiss began to form in the back of her throat, as if—

“Sister Tortoise seemed oblivious to Mother’s reaction. ‘Now, a swan is larger than a goose, but that would be to our advantage, wouldn’t it? In my experience, geese are easily intimidated. Mother, you could go outside and claim to be the head goose and order them to leave St. François alone.’

“Mother studied the notion for a moment. You could almost see her mind running with it. She relaxed her wings and her beak and her throat. ‘Sister Tortoise, you’re a genius!’

“Mother looked through the window at the geese below, strutting their silly, stiff-legged kick-walk. ‘We must hurry. Sister Mouse, come! Up on my beak.’ Sister Mouse jumped up, and it looked as if Mother had a stubby toothbrush moustache. She marched onto a tree limb overlooking the forest floor, and holding her right wing up, she boomed, ‘Achtung!’”

Eva put a finger to the space between lip and nose, a pseudomoustache, as she spoke Mother’s lines. The girls’ giggling turned to raucous laughter.

“The geese looked up, and their eyes popped. They cried, ‘Our Führer!’

“With Sister Mouse on her beak and wild wing flapping and loud ranting, Mother Swan had the geese spellbound. She roared, ‘I command that you keep clear of these parts. I will personally see to things here. Pity any goose who ignores my order! You are dismissed. Raus!’

“Mother kept up her flamboyant wing movements and guttural blusters until, in a cloud of feathers, dust, and honks, all the geese had fled. Then she strutted back into the chapel, to the cheers and adulations of every wren.”

St. Sébastien’s girls likewise broke into cheers.

A minute later, Clarisse pulled Eva aside. “In your fairy tales, Goldilocks, good may triumph. But you know, real life hardly ever works that way.”

“In real life who’s to say what good is?” Eva replied. “What matters to me is, for the moment at least, my fable’s sent fear and uncertainty scurrying off with my geese.”

“‘With my geese,’ Blondie?” Clarisse smiled sweetly. “Or should I say, Fraulein?”

Late that afternoon, Mother announced that all the students should be in their dinner seats twenty minutes ahead of the usual 6:30 time. Everyone knew that Sister Arnaude had ridden her bicycle to get the news in Lefebvre. Anticipation bubbled.

Virtually every girl was seated by 6:00, rumors passing from student to student like answers to geometry homework. Camille’s was the most repeated. “After his success with U-boats in the Atlantic, they say Monsieur Hitler now turns the idea against us. He’s unleashed a fleet of underground vehicles, burrowing like moles under France and Belgium. Whenever they like, these U-Wagens as the Boche call them, pop to the surface to unleash death and destruction. It’s true; I swear on my braids! If you doubt me, put an ear to the ground. See if you don’t hear a faint rumbling.”

At 6:10 precisely, Mother Catherine came in. Quick as a radio unplugged, the room went silent. The eyes of every girl seemed fixed on Mother’s lips, as if seeing the words formed would bring their message better or faster.

Eva took in the nun’s countenance. Framed by her veil, Mother’s was a striking face. Even from across a room, her sparkling eyes ensnared one’s attention like Cassiopeia’s stars on a clear night. Eva liked her mouth, which could be anything from soft, even sensuous, to resolute. Mother’s nose was long and pointed, but slender, giving an elegant line to her face. She was tall and slim and moved with such grace that she seemed to glide an inch above the floor. Camille, who’d been at St. Sébastien longer than any other girl, swore that before her vows, Mother had been a silent film star—that she’d seen her on a movie poster. No girl doubted it.

Mother Catherine started with the sign of the cross and a prayer. She related the day’s news, emphasizing that most of the actual fighting was far west of them. She ended on an optimistic note. “Remember our patron saint. Each of you is a daughter of Sébastien, who defied a Roman emperor and his army of occupation. When they tried to silence his opposition with a rain of arrows, his spirit prevailed. And when Fourteenth Century Europe was enveloped by the Black Death, a foreshadow of the plague of war threatening us now, Sébastien protected the faithful. Pray that the French, the British and the Germans honor our wish for exclusion from their fight. But most of all, my flowers, maintain hope. Remember that the God who counts the tiniest wren will not forget you.”

When Mother said the word “wren,” Eva thought she saw the nun wink at her.

At precisely 6:30 the dinner meal was served. Potato and leek soup, coarse bread, butter, and cheese, with tea instead of the usual milk—the first of many changes to come.

Filthy and Pristine

On the third day after the invasion, the mayor’s wife bicycled to St. Sébastien and rang the bell at the convent’s entrance.

Sister Martine opened the door and eyed the beads of sweat on the visitor’s brow. Madame Beaugarde was an ample woman stuffed into a gray wool suit.

“Good day, Sister.” Madame Beaugarde was puffing. “I’ve come in an official capacity to confer with Mother Catherine.” She pulled a handkerchief from her sleeve and patted her face and throat. “Oh my. So warm this morning. And me with only a bicycle since our motorcar won’t run.”

“Good morning, Madame. Please come in.” They walked to the reception parlor where a student in a long white apron copied figures into a ledger. “That will do, Bébé,” The girl curtsied and left. Sister followed her out. “I’ll fetch Mother.”

Mother Catherine came in and nodded. “Welcome to St. Sébastien, Madame. How are you this morning?

“I’m fine, Mother Catherine, thank you.”

“May we offer you tea, Madame?”

“I don’t care for tea on such a warm morning. Besides, I come on an official matter, not a social one.” She straightened her hat, a tired, small-brimmed, black felt affair topped with faded silk violets. Nervously she took a paper from her waistband. “The mayor wrote me notes so I shan’t forget anything.” Her hands shook as she unfolded the sheet. “Mother Catherine, you know that there is to be an assembly in the town square for all of us tomorrow?”

“So I have heard.”

“My husband wishes there to be no misunderstanding about the regimen for the event.” Madame Beaugarde paused as if expecting an invitation to proceed. When Mother kept silent, she cleared her throat and read. “The assembly will begin at noon. You and the sisters and girls must all be in place at that time. There will be no absences.” The woman’s finger led her eyes along the written lines. “No patriotic or anti-German displays will be tolerated. The reception afforded speakers and other dignitaries will be cordial.” She looked up from her notes and added in a defensive tone, “You know, I am just the bearer of the message. But, Mother Catherine, much does depend on Lefebvre’s attitude.”

Mother replied, “I have only the deepest animosity for the gang that violates our soil. But though I willingly place my own fate in the hands of God, I’ll do nothing to compromise the safety of my little ones. We of St. Sébastien will be mute witnesses to tomorrow’s black farce.”

Madame Beaugarde rose. “In that case, good day, Mother Catherine. I will find my own way out.” She stopped at the parlor door and turned. “You know, I didn’t invite the Boche in. None of us did. But they’re here and like hornets under the eaves, stirring them up does none of us any good.”

“Indeed,” Mother replied. “But conscience and honor dictate that they also not be made to feel welcomed.”

Madame Beaugarde huffed off.

The next morning, led by the nuns and walking two-by-two, the girls of St. Sébastien departed the school for the trek to Lefebvre. They walked in uncharacteristic silence along the country lane toward the village. Mother, her own mood one of brooding, was content to have the quiet, though she felt guilty for that.

About a kilometer from town, from behind her, Mother heard a lone voice begin singing softly. “Frère Jacques, Frère Jacques. Dormez vous? Dormez vous?” Mother looked back. It was Eva singing.

Doing the first verse alone, Eva’s face radiated courage. “Come now, girls,” she called, “remember how we deal with geese. Hold those heads high and sing along! Frère Jacques, Frère Jacques. Dormez vous? Dormez vous?” By the second verse, every student had joined in, singing the round. There were even some smiles.

When all the singing had started, Sr. Eusebia looked back at them, her eyes wide in alarm. She was opening her mouth to silence them when Mother caught her eye and stopped her with an index finger raised to the lips.

So, the girls sang on, even as they marched into the village square at 11:45 to take their position. The townspeople had already assembled before the small dais that had been hastily erected in front of the Hôtel de Ville. As she and the girls stood facing the platform, Mother felt the sapped faces of the townsfolk to her right and left dragging her spirit down. But it soared as she thought of her girls’ arrival and saw them now arrayed behind her in military-straight ranks, each girl with head held high, standing resplendent in her uniform of snow-white blouse, blue wool jumper, white knee-high stockings, and shiny black shoes. Today it will be the children who teach their elders, Mother thought as she circled her troop, nodding encouragement.

Behind her students, Mother paused to drink-in Lefebvre’s town square a last time before its debasement. With her toe, she traced the edge of an ancient cobblestone, polished smooth over centuries by the scuffs of wheel, foot and hoof. In the square’s center, she gazed for a moment at the bronze statue of the she-fox Liberté defending her pups from a pack of weasels. On the north edge of the square, she viewed the red brick and white marble façade and the baroque-sculpted gable of the Hôtel de Ville. Facing east, her eyes caught the sun glittering off the gold leaf covering the ornate Guild House, between the half-timbered post office and the Nagelmackers Bank. She turned south, to the crouching granite soldier of the Great War memorial and Saint Marc’s, the dark Romanesque church where Father Celion was pastor. And west, to the colorful signs and awnings of the small shops—the bread bakery, the pastry bakery, the smoked meats shop, the butcher shop, the fruit and vegetable shop, the chocolatier, the wine merchant, and the café with its white-clothed, outdoor tables. Her eyes found the road between the café and Saint Marc’s leading to the bridge built in Roman times, the Pont de Pierre, saddle on the back of the mighty River Meuse. “A way out of town!” Saying it aloud felt empowering to Mother. Finally, scanning faces of the townsfolk, she shook her head at the grim expressions, the tear-streaked cheeks. Lefebvre, you’ve been a quiet town who’s dealt with outsiders on your own terms or not at all. Today that changes. We all change. Adieu, Lefebvre.

On the platform a few meters away, two Nazi swastikas ominously sandwiched a Belgian flag. The town’s mayor, its constable, and its doctor sat on the dais looking as happy to be there as hungover men at the opera. Next to them, looking positively ecstatic, was a pro-Nazi Belgian, Leon Le Deux. And there was another civilian, a stranger, with a razor-sharp nose and the dark, darting eyes of a hawk. He wore a swastika armband.

Waiting for things to begin, Mother Catherine considered the scene before her—how it teemed with contradiction. On the one hand, the Nazi dais leering at her. On the other, reflected off cobblestones still wet from the early morning rain, the impressionistic image of the colorful shops lined up to the west—for Mother, an airy watercolor like ones she’d done as a girl in Paris. The first debauching the second like an animal carcass rotting in a glacial mountain stream. It was ugly and beautiful. Filthy and pristine.

Mother’s thoughts were interrupted when Mayor Beaugarde scurried up. “Oh Mother Catherine, your little angels sang so beautifully as you approached the square. I am to say Monsieur Le Deux invites you and your girls to stand around the speakers’ dais and serenade our distinguished guest, Herr Reeder, before the program.” The mayor turned to Le Deux seated on the dais and bowed. Le Deux smiled broadly and nodded back. “You see, he sends a greeting to you and your lovely charges. For the sake of Lefebvre, may I say you’ll do it, Mother?”

Mother Catherine put a hand on the mayor’s shoulder and drew him near. “See how nicely he shows his fangs. Please tell Herr Le Deux that I would sooner swallow a bucket of broken glass than sing for his German master.”

The mayor turned pale. “Oh please, Mother. It will only get more difficult for—”

The nun cut him off. “Tell him we’re fresh out of songs.” The steel in her voice made clear the discussion was over.

The mayor slinked back to the dais. He spoke timidly to Le Deux. For a moment Le Deux did nothing. Then he glared darkly at Mother Catherine.

At noon, Le Deux strode to the front of the dais. His festive look had returned. After a moment to relish the scene, he gave a sharp nod to the Wehrmacht officer standing next to the dais. The oberleutnant, a fish-faced man with an empty left sleeve pinned to his side, unholstered a Luger pistol and fired a signal shot. Every neck tensed as the report dashed out to each corner of the square and returned, a hollow pop.

At the far end of the square, next to the church, the canvass back covers on two transport trucks flew up and out poured twenty-one German soldiers. They formed four tight columns, a massive sergeant with a ceremonial sword in front and to the right. In quick succession the sergeant brought his troop to attention, had them shoulder their rifles, and moved them forward toward the assemblage. Half-way across the square, the sergeant bellowed a command, and as one, the unit changed from their quick time march to the high step parade march. Mother shuddered, thinking they’d been choreographed carefully as a Russian ballet, a group of men moving with the menace of a single predatory beast. She mentally dissected the elements that combined to wield such power: The black and red swastika banner out front. The uniforms tight and gray. Black helmets glittering in the midday sun. Shiny bayonets pointing skyward, threatening even the heavens. Polished, black jackboots swinging up in their ominous goosestep and slamming back down onto the cobblestones, each slam making a single report. And the soldiers’ carriage—bodies rigid, except for the machine-like legs and the swinging right arms.

Mother Catherine turned to nod encouragement her students. Her gaze fixed on Françoise and Eva standing together—Françoise struggling to hold back her sobs and Eva with her arm around her friend’s shoulder. Mother prayed, my little Eva, always so strong, always so confident. Lord, give me Eva’s strength. Eying the she-fox, she whispered, “Liberté, en garde! The weasels approach.”

When the phalanx was close, Mother could see faces under the helmets. They looked young as altar boys, she thought. Young, but without youth. With each left stride, right fists pumped up to strike left breasts in perfect unison, almost like her girls saying their mea culpas. But rather than acts of contrition, she knew these were intended to strike fear into the hearts of onlookers. And she could see by the hopeless looks on the townsfolk’s faces that the show was effective. Faces tell it all. Even the soldiers’ taut faces, which moved only in a twitch of the cheek flesh, each one a shock propelled up through the body by the percussion of boot on stone. It was for her a grim reflection of the vile shocks being felt by Lefebvres all over Europe.

The troop took positions on each side of the dais, and Le Deux, his chin jutting, spoke again. “My fellow Belgians, Heil Hitler! I tell you forthrightly, we are in for changes, just as is the rest of the world. But I believe, and I think you must believe also, that these will be changes for the better. I am pleased to introduce Herr Eggert Reeder, the Fuhrer’s Militarverwaltungschef-ernannt, designated head of the Military Administration. His message is important. Listen carefully.” With a grand sweep of the arm, Le Deux handed the stage to the man with the dark eyes. “Herr Reeder!”

Reeder moved cautiously to the fore, sizing up the people of Lefebvre. He began with a stiff arm salute. “Heil Hitler! Today dawns a new era for your most charming village, just as events in the west signal the dawn of a new Europe. A cleansed Europe. Even as I speak, Panzer units of the Third Reich are breaking through French defenses.” Reeder’s French was technically perfect, but his German accent made it succulent mussels ruined by too much salt. “People of Lefebvre, you all know society needs rules. New, better rules will replace some of the old ones. But a few new rules aren’t such a big deal, are they?”

In the students’ ranks, Françoise turned questioningly to Eva, who gazed serenely ahead.

The speech continued with a summary of the changed chain of authority, the rationing programs, and other elements of the new order. Finally Reeder concluded, “These rules are for our collective good. I close with a warning. Do not oppose the course of history. We deal especially harshly with certain offenses: black marketeering, harboring enemy persons, and resistance to proper authority.” Mother thought she saw Reeder glance toward St. Marc’s. “A complete set of the new rules will be promulgated. Make yourself aware and ensure compliance. Heil Hitler!” Reeder’s eyes darted over the crowd, judging the spirit with which his comments were received.

It was just as Reeder turned away to shake hands with the others on the dais that it struck Mother Catherine—she hadn’t seen Father Celion in the square. She had been so concerned with her students that she hadn’t thought to look for him.